Parents who sent their daughters to Bryn Mawr College in its earliest years may have done so with apprehension. In the late nineteenth century, social propriety required young women to be supervised and guided. Bryn Mawr’s founder, Joseph Wright Taylor, certainly shared this concern. In his will, which was drafted in 1877 and articulated the terms of his bequest to establish a Quaker women’s college, Taylor calls for a Quaker gentlewoman to watch over the domestic spaces of his collegiate vision. He proposes that the Trustees

… consider the propriety of appointing a few wise, religious, enlightened, and superior female Friends [Quakers], to visit and to have immediate and direct care and oversight of the students, the selection of officers and the domestic arrangements at the Institution subject to the Trustees. 1

M. Carey Thomas (the first Dean of the Faculty and Second President of the College) changed the title “lady in charge” to “warden” in 1901, but the role had been evolving since its conception.2 In a conversation that took place in 1884 between the Board of Trustees and Thomas concerning Taylor’s will, they discuss the nature of the lady in charge, referring to her as a “mistress of the hall.” 3 They restate what Taylor had written, but a note at the end of the document reads, “It is hoped that in future days our own graduates may increase the number of possible mistresses of halls.” 4 We learn two things from this statement. First, that from the beginning, plans were already being made to change the position of lady in charge, with a desire to make the role more explicitly academic by hiring college graduates. Second, that the Board of Trustees envisioned Bryn Mawr’s graduates as the future generation of “Quaker gentlewomen,” worthy to serve as models and guardians of Bryn Mawr’s students.

While conducting research on the dorm mistresses, I started to imagine that Taylor might have had specific women in mind for the role of lady in charge when he wrote his will, someone like his own mother, or his sister, Hannah Taylor. Yet Bryn Mawr’s lady in charge is not found in any single box or folder in the College’s archive. Instead, the evidence for her roles and identities is scattered throughout. There is no complete account, but rather archival “scraps.” The project of telling her story is like assembling a scrapbook, and my research led me from Board Minutes to personal letters, floorplans, scrapbooks, newspaper articles, lady’s magazines, legal documents, and photographs. The lady in charge hints at a very early Bryn Mawr that does not completely revolve around rigorous academic standards. Instead, the position reflects the ambitions of Taylor and the original Board of Trustees to preserve a domestic atmosphere for the students.

Initially, the Board of Trustees tried to poach Fanny A. Dart from Smith College (Fig. 1). Dart was the lady in charge of one of the student cottages at Smith, Hubbard House, during the 1870s and 1880s. According to the Bryn Mawr Executive Board minutes, Dart was hired by Bryn Mawr, but never started the position. The reason is not indicated in the archive. We know that she was consulted on matters of dorm life by Bryn Mawr’s founders, and that she was hired by the Board of Trustees with a salary of $700 per year (Smith paid Stokes $600 per year).5 After touring Smith in 1884, M. Carey Thomas made the following comment about Dart, “It will be observed that this lady in charge is at once steward, housekeeper, and matron.” 6

Dart is specifically referenced in the Executive Board minutes in early 1884. She had been hired as Merion’s first “lady manager,” and the Board notes a brief list of her duties. This paragraph is the most detailed description of the role in Bryn Mawr’s archive. It explains how the woman in this position

shall have charge of the household management, keep accounts of all expenditures and receipts for the same; and who shall have the oversight of the conduct of the students resident in her cottage. She shall act towards them the part of a House-mother, and be responsible for the discipline of those under her care. 7

The lady in charge thus adds a new dimension to dorm life during Bryn Mawr’s earliest years. From the archive we can start to imagine her relationship with students.

The scrapbooks of Elizabeth Crocker Lawrence, a student at Smith during the early 1880s, records a few reminiscences of Fanny Dart. There were receipts and course lists written by Dart, as well as a passage from the 1881-1882 book describing a birthday celebration for “Mrs. Dart” organized by the students of Hubbard House. Lawrence writes how “A Mother Goose Carnival was the order … all of the characters marched down to the parlor where they were introduced to Mother Hubbard by Mother Goose.” 8 This description alludes to a close-knit household with Fanny Dart acting as a mother-figure. Although Dart never worked at Bryn Mawr, in addition to providing consultation to M. Carey Thomas when she toured Smith, she also provided advice to the architect of Merion Hall, Addison Hutton. Hutton, in an 1884 letter, writes “a lady whom I had looking at Merion Hall and who has been acting as Lady Manager at Hubbard House, assures me that the pantry space is much too little.” 9 A sense of the close relationship of Smith students with the Lady Manager of their cottage is conveyed by a photo dating to 1888 and depicting residents of Hatfield House with their Lady Manager, Fanny C. Hesse (Fig. 2).

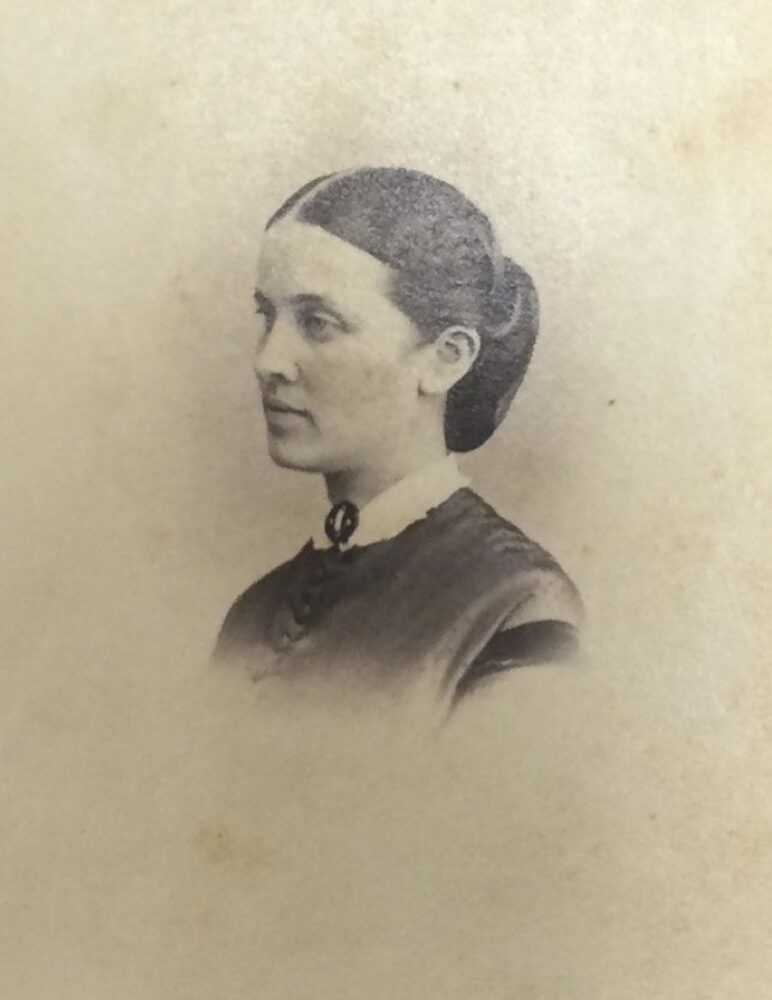

The first successful hire of a lady in charge for Merion Hall was Hetty Newlin Stokes (Fig. 3 and 4). A Quaker, Stokes was acquainted with the Board of Trustees, because she was a member of the Stokes-Evans-Cope family associated with Haverford. Stokes was considered refined and educated, the 1850 census recording her as being away at school, and the 1860 census listing her occupation as “gentlewoman.” 10 The ladies in charge tended to remain close to their own families, often prioritizing familial obligations over their role at Bryn Mawr, as evidenced by Stokes leaving Bryn Mawr in October 1887 on account of her family’s need. The Board of Trustees recorded that “for two years [Stokes] has had charge of Merion Hall, felt that she must resign her position in obedience to the claims of her family.” 11 After resigning, Stokes spent the next decade as a companion to her sister, Eleanor Evans.

Tracing Stokes’ lineage through census records gives us an idea of the upbringing and lifestyle of an early lady in charge. Stokes’ father, John Stokes, was a Dry Goods Merchant. In 1850, his estate was valued at $6,000 (approximately $227,904.62 by today’s standards).12 By the 1860s, the value of her father’s real estate had increased to $7,500, and his personal estate to $500.13 The ladies in charge were privileged, white “gentlewomen” from well-off families and were typically raised in households with some domestic staff. Understanding their social status allows us to distinguish between the lady in charge and other staff within the dorms. The lady in charge was not perceived as a domestic worker, but instead as an instructor in domestic lifestyle and personal comportment. The lady in charge also likely supervised the dorm staff. In “Information for New Wardens” (dating to after 1901), M. Carey Thomas wrote “rules in regards to servants,” which mention how the warden hires and supervises “staff and assistants,” including housekeepers, cooks, and maids, among others.14

Fig. 4. First class of Bryn Mawr College. Hetty Newlin Stokes seated second row, far right. Bryn Mawr Class of 1889, c. 1886, 1 photograph: black-and-white; 28.50 x 36.40 cm. Bryn Mawr College Photo Archives, BMC-Photo Archives, Series I: Photographs, PAE_CPOS_002_01.

The first non-Quaker lady in charge, Elizabeth Lore, was hired in 1887.15 Lore, like Stokes, resigned from the position after only a few years due to familial obligations. Although a Methodist, Lore still had connections with the Quaker founders of Bryn Mawr. In a letter from M. Carey Thomas to Mary Garrett written in 1887, Thomas reports, “in Merion Hall we have appointed Bessie Lore, an old Howland graduate.”16 The Howland Institute, a Quaker boarding school, was where Thomas completed her secondary school education from 1872 to 1874. Thomas recollects intimate details of Lore’s school years, identifying her as a close friend. What separates Lore from Dart and Stokes is her age. Lore was at least a decade younger than these earlier ladies in charge.

Other ladies in charge of Merion Hall from the 1880s and early 1890s included Emily H. Pim and Lydia V. Smith, who switched in and out of the position between 1888 and 1891. Smith died unexpectedly in 1891 and it is unclear why Pim decided to leave Bryn Mawr. If we include Fanny Dart, between 1884 and 1889, Merion Hall went through five ladies in charge.

Anna Mary Wistar was hired in 1886 as Radnor Hall’s first lady in charge, but withdrew from the position due to bad health. She was a member of another respected and influential Quaker clan, the Wistars, who were family friends of the Taylors. When Radnor Hall (Fig. 5) opened its doors to students in 1887, it did not initially have a lady in charge because Wistar had resigned last minute. Instead, Radnor’s first official lady in charge was Hannah T. Shipley. Shipley, who was in her thirties at the time, remained at Bryn Mawr only four years, resigning in 1891, and was replaced by Susan S. Chase. In 1894, Shipley and her sisters, Elizabeth and Katharine, established the Shipley School. Initially founded as a preparatory school for Bryn Mawr College, Shipley is still in operation today and located next door on Yarrow Street. Hannah T. Shipley introduced a trend of ladies in charge subsequently founding preparatory schools. Sophie Kirk, who was made lady in charge of Merion Hall in 1891, later co-founded the Misses Kirk’s School.

We know very little about how the lady in charge interacted with domestic staff. A photograph thought to be of Sally Brown—a member of the service staff in Merion Hall—depicts her in Sophie Kirk’s finely appointed room (Fig. 6).17 The image offers a glimpse into the living space of a lady in charge, as well as a domestic worker’s role in that space. Although Kirk herself is absent from this photograph, dynamics of class and race are not. While a paid employee of the College, the lady in charge was attended by the dormitory’s domestic staff, and she was in a position of power over them. There is very little information in the archives explicitly relating to the lady in charge, but there is even less concerning the domestic staff employed during this early era.

Information about the life and work of the lady in charge is distributed throughout the archive. Just as she is situated in between faculty and student and staff, she is also positioned in between presence and absence in the institutional record. In many places, we can catch glimpses of her, but a full picture never comes into focus.18

Works Cited

Primary Sources

1850 United States Federal Census [database online]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2009. https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/discoveryui-content/view/5096305:8054?tid=&pid=&queryId=0b5b8ea9c20d3e8cf4378590f7182bcc&_phsrc=jSE294&_phstart=successSource.

1860 United States Federal Census [database online]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2009. https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/discoveryui-content/view/54128753:7667.

Addison Hutton Papers. MC-1122. Haverford College Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford, PA.

Board of Trustees and Directors, 1884-1905. BMC.CA.RG2, Bryn Mawr College Archives, Record Group 2: Governing Boards. Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

Executive Committee. BMC.CA.RG2, Bryn Mawr College Archives, Record Group 2: Governing Boards. Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

Hetty Newlin Stokes. c. 1866. Photograph. Stokes-Evans-Cope Family papers, Box 4, Folder “Photos from album, numbers 1-24” HC.MC-1169. Haverford College Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford, PA.

Scrapbook of Elizabeth Crocker Lawrence. Elizabeth Crocker Lawrence Papers, smith_ca_80-02_b1411_f051, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts. https://compass.fivecolleges.edu/object/smith:13834 Accessed 28 April 2022.

Taylor Family Papers. MC-962. Haverford College Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford, PA.

M. Carey Thomas Papers. Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

Secondary sources

Anonymous. “College Girl Manners: Peculiar Dangers Against which Parents May Fortify their Daughters.” Good Housekeeping 12 (1902): 469-470.

Horowitz, Helen Lefkowitz. Alma mater: Design and Experience in the Women’s Colleges from Their Nineteenth-century Beginnings to the 1930s. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1993.

Notes

- Joseph Wright Taylor, c. 1870-1880, Will (with codicil) of Joseph Wright Taylor. Certified copy. Taylor Family Papers, HC.MC-962, Box 7, Folder 9, Haverford College Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford, PA.

- Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz, Alma Mater: Design and Experience in the Women’s Colleges from Their Nineteenth-century Beginnings to the 1930s (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1993), 119.

- The terms “mistress” and “lady in charge” seem to have been used interchangeably, especially during the years when plans for Bryn Mawr were being made. The official title, however, was “lady in charge.”

- M. Carey Thomas, 7 June 1884, Discussion of Dr. Taylor’s Will, Thomas Papers, Office Files, Box 27, Folder 34, Bryn Mawr Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

- M. Carey Thomas, n.d., Report Presented by M. Carey Thomas, Dean of Faculty, to the President and Trustees of Bryn Mawr College, M. Carey Thomas Papers, Office Files, Box 4, Folder 24, Bryn Mawr Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

- M. Carey Thomas, 7 June 1884, Report Presented by M. Carey Thomas, Dean of Faculty, to the President and Trustees of Bryn Mawr College, M. Carey Thomas Papers, Office Files, Box 4, Folder 24, Bryn Mawr Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

- Executive Committee. BMC.CA.RG2, Bryn Mawr College Archives, Record Group 2: Governing Boards, Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

- Lawrence, Elizabeth Crocker, 1861-1951. “Scrapbook of Elizabeth Crocker Lawrence.” Smith College. 1880-1881. College Women. Web. Accessed 4 May 2022. https://www.collegewomen.org/node/18348

- Addison Hutton, Letterbook, 1905-1909, Addison Hutton Papers, HC.MC-1122, Box 1, Folder 5, Haverford College Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford, PA.

- U.S. Census Bureau, 1850 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2009. https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/discoveryui-content/view/5096305:8054?tid=&pid=&queryId=0b5b8ea9c20d3e8cf4378590f7182bcc&_phsrc=jSE294&_phstart=successSource; U.S. Census Bureau, 1860 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2009. https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/discoveryui-content/view/54128753:7667.

- Board of Trustees and Directors, 1884-1905. BMC.CA.RG2, Bryn Mawr College Archives, Record Group 2: Governing Boards. Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

- U.S. Census Bureau, 1850 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2009. https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/discoveryui-content/view/5096305:8054?tid=&pid=&queryId=0b5b8ea9c20d3e8cf4378590f7182bcc&_phsrc=jSE294&_phstart=successSource.

- U.S. Census Bureau, 1860 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2009. https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/discoveryui-content/view/54128753:7667.

- M. Carey Thomas, n.d., Information for New Wardens, M. Carey Thomas Papers, Office Files, Box 29, Folder 60, Bryn Mawr Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

- Horowitz, Alma Mater, 373.

- M. Carey Thomas to Mary Elizabeth Garrett, 11 November 1887, BMC-CA-RG1-1DD2, Reel 15b, Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

- Sally Brown is the subject of a section in the exhibition “Who Built Bryn Mawr? A Beginning” (2021). https://www.canva.com/design/DAEWarnafGI/YkaA5I5amI8MXKfCa6x14Q/view?utm_content=DAEWarnafGI&utm_campaign=designshare&utm_medium=link&utm_source=publishsharelink#1.

- Because the lady in charge can be found in a variety of places in the archive, my research was a collaborative process. I would not have been able to write this blog post without the research and contributions of others. Throughout my research process, Allison Mills (College Archivist, Bryn Mawr College) and Professor Alicia Walker (Academic Co-Advisor for Who Built Bryn Mawr? 2022) were incredibly helpful in pointing me in the right directions. Alexis White (Bryn Mawr graduate student and Academic Co-Advisor for Who Built Bryn Mawr? 2022) and fellow Research Assistant Esmé Read also helped with gathering information and guiding my process.