Umeko Tsuda was the first student of East Asian descent to attend Bryn Mawr College. A native of Japan, Tsuda had lived for many years in the United States and was educated in the American system. Although Tsuda’s matriculation depicts advancements in the inclusion of international students and Asian women at Bryn Mawr, it must be contextualized in national and international ideologies of racial superiority and Westernization. Indeed, it must be understood within the context of a Quaker social reform project, which was only possible in Japan after 1873, when the government lifted its ban on Christianity.

Japan’s Meiji era (1868-1912) ushered in policies endorsing mass industrialization and modernization, known as bunmei kaika (“civilization and enlightenment”). Seeing their own values and investments mirrored in Japan, Western elites categorized the Japanese as a civilized race. In Philadelphia, the Women’s Foreign Missionary Association of Friends hosted Tsuda to give speeches and “parlor talks” about the subservient social position of Japanese women. These Quaker women, including Mary Morris, wife of Haverford Trustee Wistar Morris, helped Tsuda raise funds to establish an American Scholarship for Japanese Women in the fields of teaching, medicine, and industrial work.

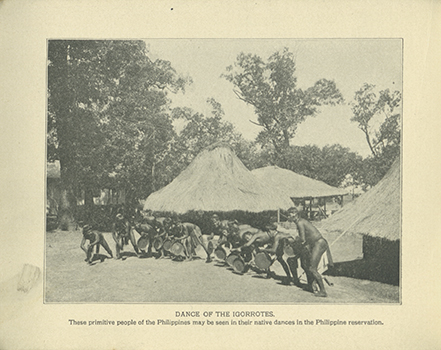

Simultaneously, other Asian peoples were judged to be primitive or unenlightened. As the United States expanded its imperial ambitions in the late nineteenth century, Americans were especially invested in the subordinating racialization of the peoples of the Philippines, which was ceded to the United States by Spain in 1898.

Learn more about Umeko Tsuda in “Who Built Bryn Mawr? A Beginning”

Read exhibition co-curator Tessa Famatigan’s reflection on this photograph and her own positionally to this history as a Filipino American student at Bryn Mawr

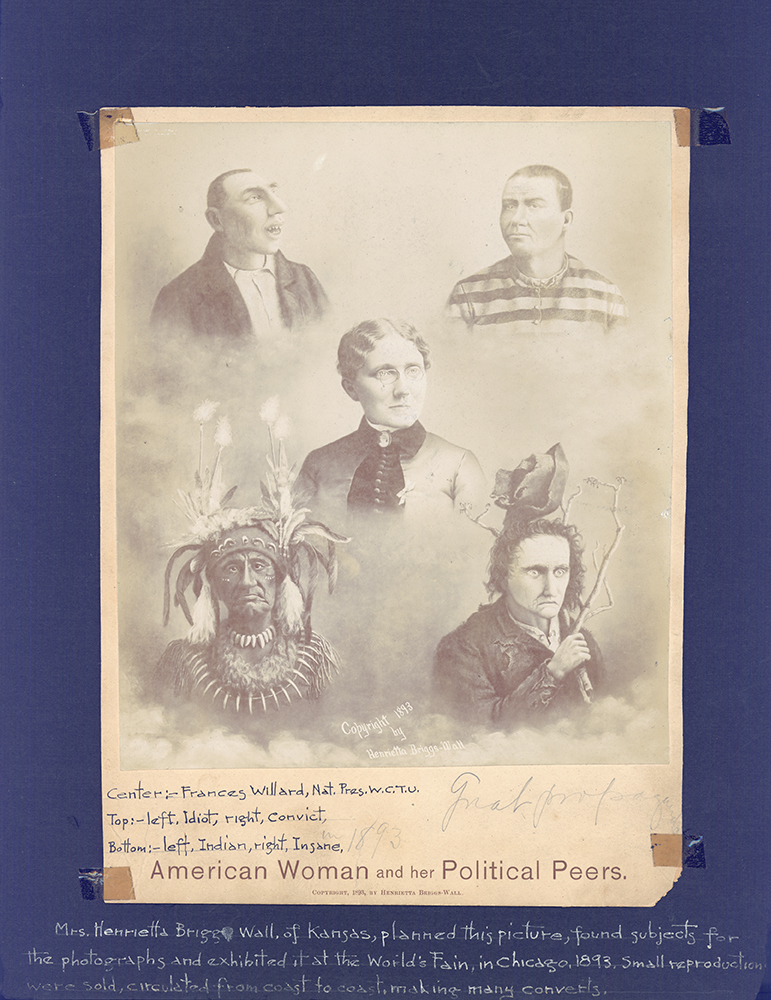

Center: Frances E. Willard (1838 – 1898), President of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union

Clockwise from upper left: an “Idiot”, a “Convict”, an “Insane” man, and an “Indian”

This image promoting white women’s suffrage was displayed at the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago and distributed internationally. It satirically compares their political powerlessness to that of other disenfranchised groups perceived to be their inferiors. Instead of imagining white women’s advancement through solidarity, this image endorses female enfranchisement by perpetuating frameworks of exclusion and subordination.

How can we understand conflicting notions of inclusion when they are still tied to systems of exclusion?