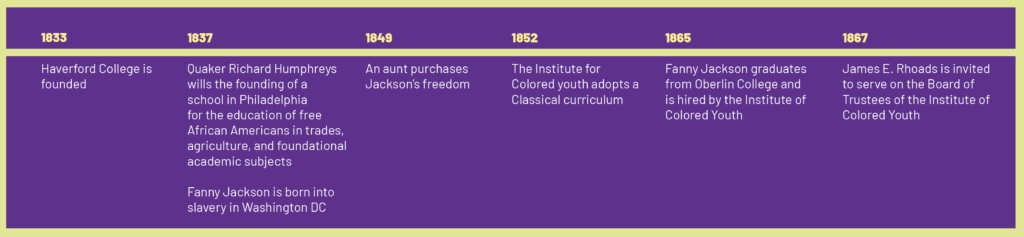

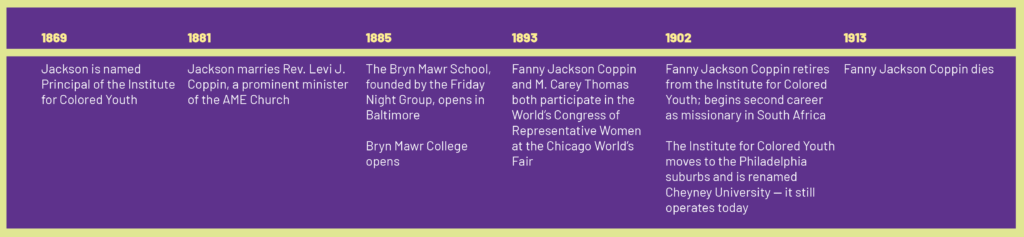

The Institute for Colored Youth in Philadelphia was the first high schools for African Americans in the United States, and the first to employ exclusively Black teachers and administrators, albeit overseen by a white Quaker Board of Managers. Initially offering an Industrial Curriculum, it reorganized in the pre-Civil War era to train African American teachers in a demanding Classical Curriculum that foregrounded Greek, Latin, philosophy, mathematics, and science. Fanny Jackson Coppin, an 1865 graduate of Oberlin College, was among its early administrators. A woman of great academic achievement and national renown, Jackson Coppin was at the center of nineteenth-century African American education and social reform, especially for women.

Joseph W. Taylor willed the Institute for Colored Youth a modest donation. Abolitionist and Quaker philanthropist Benjamin Coates offered James Rhoads a position on the Board of Trustees, but Rhoads declined because of the pressures of his existing philanthropic commitments. In many ways, M. Carey Thomas and Fanny Jackson Coppin shared parallel ambitions and successes. Yet, there is no indication that the Institute and Bryn Mawr or their administrators ever collaborated, formally or otherwise.

Despite offering a curriculum that would have prepared their students for the demands of Bryn Mawr College, the Institute of Colored Youth was never considered to be a feeder school. Instead, in 1885, the “Friday Evening Group” founded a non-denominational secondary school in Baltimore to prepare white students for Bryn Mawr College’s formidable entrance exam and rigorous Classical Curriculum. Funded generously by Mary Garrett, the school mirrored Bryn Mawr in its richly endowed buildings, state of the art pedagogic resources, and aesthetic refinement.

“We, as you know, are classed among the working people, and so when the days of slavery were over, and we wanted an education, people said, ‘What are you going to do with an education?’ You know yourselves you have been met with a great many arguments of that kind. Why educate the woman – what will she do with it? An impertinent question, and an unwise one. Rather ask, ‘What will she be with it?’”

Fanny Jackson Coppin, speech delivered at the World’s Congress of Representative Women, Chicago World’s Fair, 1893. The World’s congress of representative women: a historical résumé for popular circulation of the World’s Congress of Representative Women, convened in Chicago on May 15, and adjourned on May 22, 1893. Chicago: Rand, McNally, 1894, 715-717.

“Our idea of getting an education did not come out of wanting to imitate any one whatever. It grew out of the uneasiness and the restlessness of the desires we felt within us: the desire to know, not just a little, but a great deal. We wanted to know how to calculate an eclipse; to know what Hesiod and Livy thought; we wished to know the best thoughts of the best minds that lived with us; not merely to gain an honest livelihood, but for a God-given love of all that is beautiful and best, and because we thought we could do it.

Fanny Jackson Coppin, speech delivered at the World’s Congress of Representative Women, Chicago World’s Fair, 1893. The World’s congress of representative women: a historical résumé for popular circulation of the World’s Congress of Representative Women, convened in Chicago on May 15, and adjourned on May 22, 1893. Chicago: Rand, McNally, 1894, 715-717

This Italianate brick building on 9th and Bainbridge Streets in Philadelphia was the home of the Institute for Colored Youth from 1865-1902. It still stands today.

How would Bryn Mawr College be different if its leaders had seen fit to recruit female graduates from the Institute for Colored Youth?