“So that it seems to me Bryn Mawr should offer to its students, who are resident there, a home modelled after the domestic band beneath the parental roof. Then too may it be able to carry on the cultivation of those tastes, habits and manners that adorn a home, without entailing suffering from undue pressure and constraint… Formed to be a help meet for man, and placed beside him as his equal, her nature fitted her for a special sphere and had its special needs; and in the education of woman, that nature and those requirements must be ever kept in mind if the Divine idea is fulfilled.”

Mary R. Haines, “Womanly Education,” in Proceedings of a Conference on Education in the Society of Friends (1880)

Mary Rhoads Haines was the sister of James E Rhoads, the first president of Bryn Mawr College, and the mother-in-law of Bryn Mawr Trustee John B. Garrett. In this speech, Haines reflects the religiously conservative views of some Quakers, by positioning family as a preordained model, and cautioning that female education must sustain this model.

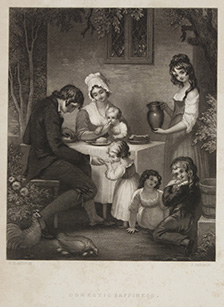

The patriarchal social order that informed Taylor’s fears was evident in diverse forms of nineteenth-century visual culture. The parents and five children in this domestic scene are not the only family present. While the mother and father attentively offer their children food and libations, chicks gather around a mother hen, and the cock protectively watches over. The blending of interior and exterior space situates these families within a natural order that promises harmony. At Bryn Mawr, Joseph Taylor and Francis King sought to create a home environment that preserved patriarchal social order, which they perceived to be natural.

Domestic Happiness, mid-19th century

Mezzotint

Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, SAR.125