The single largest Quaker philanthropic project in the mid- to late nineteenth century was the founding of educational institutions for recently liberated African-Americans. Most of these schools offered vocational curricula that taught basic writing, reading, and math alongside manual trades and agricultural skills. Conceived as benevolent endeavors by their white Quaker founders, these schools were also informed by their benefactors’ beliefs in racial separatism and superiority.

The Schofield Normal and Industrial School was founded by the Quaker educational activist Martha Schofield, who was born in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. The Schofield school provided a limited, religiously focused education, training African-Americans to be teachers and laborers. James Rhoads, the First President of Bryn Mawr, advised and supported Schofield, before and during his time at the College.

While the Quakers saw themselves as altruistic, their activism was often paternalistic, motivated by the intention to disseminate their Christian civilizing mission. In many instances, their educational philanthropy rested on beliefs that Black people were inherently inferior and naturally fit for manual labor, not advanced education.

“To you these hitherto ignorant people look for guidance of faltering steps. See to it that they are pointed in the right directions. Let it be no fault of yours if their citizenship is not marked by the beneficent results of Christian civilization, many of them so strikingly illustrated in Northern communities.”

Fourth Annual Report of the Executive Board of the Friends’ Association of Philadelphia and Its Vicinity for the Relief of Colored Freedmen, 1867

Bryn Mawr Trustees John B. Garrett and Edward Bettle and First President James E. Rhoads were members of this Association. Rhoads served as a field superintendent of schools in Yorktown, VA.

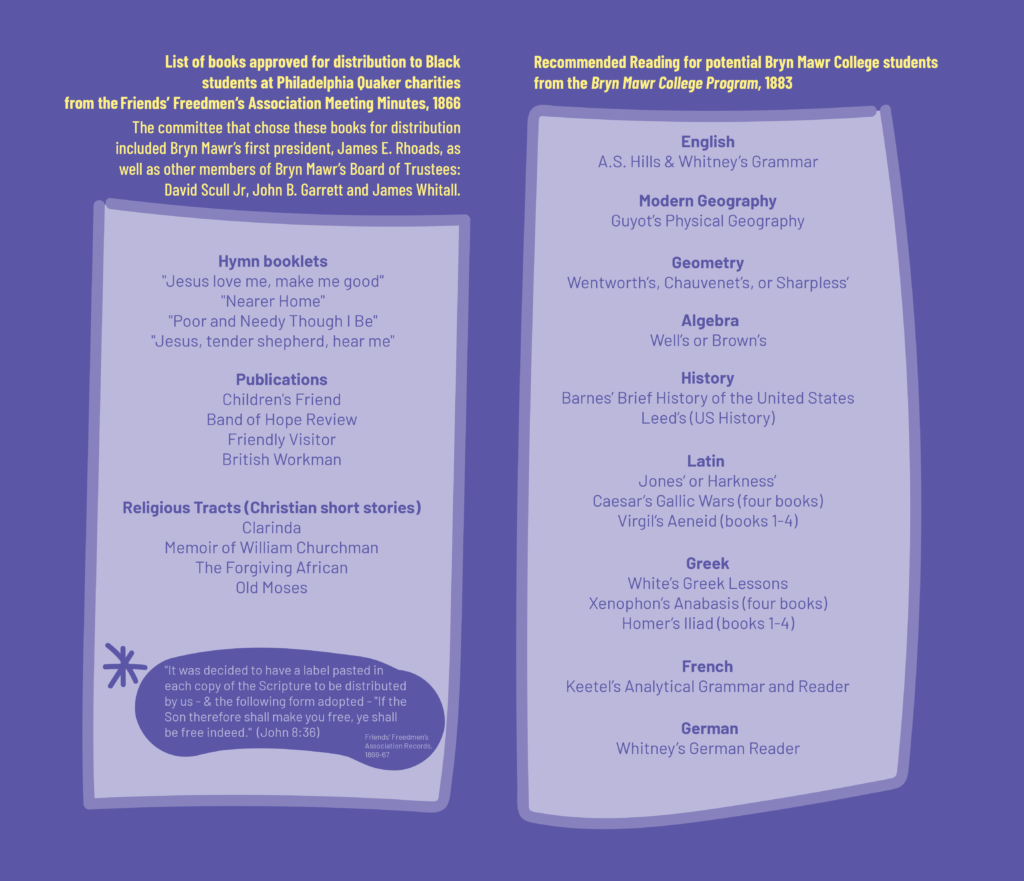

Comparing curricula

The reading list approved for distribution to Black students at Quaker schools versus the one distributed for prospective Bryn Mawr students reflects the different ambitions undergirding these educational missions. The reading list for Black students features exclusively religious work. Almost all were brief and geared toward moral edification, but in ways that subordinated Black students. In contrast, the advanced textbooks and classical works for Bryn Mawr students implied their assumed superior intellectual capacities and social refinement.