The nineteenth-century ideal of separate spheres confined women to the private realm, while men ventured into public. However, the home was a stage for a performance of propriety, order, and harmony that assumed an audience beyond the family. Middle and upper-class women were worshipped as the “angel in the house,” a nurturing, self-sacrificing figure responsible for homemaking and raising children, passive yet devoted to her husband. This so-called cult of true womanhood enjoyed tremendous popularity. While women were expected to avoid employment in the public sphere, this was often impossible for working-class women, who had to support their families.

The ideal nineteenth-century home was structured around a hierarchy of gender and class that placed the father at the head, closely followed by the wife, who controlled the domestic domain, and finally the children. Women who excelled in domesticity were often able to do so only with the labor of household staff, who worked outside their own homes to enable the realization of middle- and upper-class domestic ideals. Yet domestic staff were often made invisible by means of separate service corridors and stairwells.

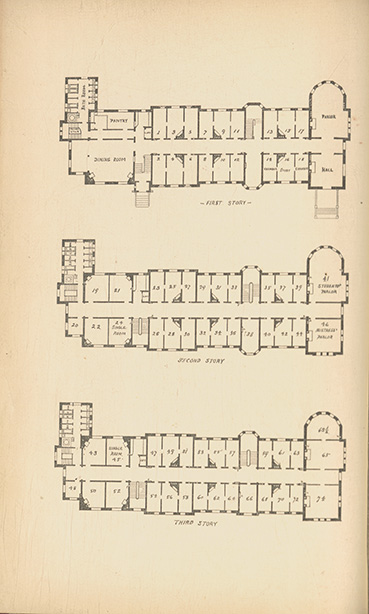

Taylor’s contract with Addison Hutton, finalized on June 9, 1879, stipulated a “home building” and a separate “economic building“ or “Annex,” which housed the dining hall, kitchens, cellars, and service staff lodgings. The Annex was never built, and its functions were instead incorporated into Merion Hall

“The civilization of our nation is unequal. It has great weakness as well as great strength. Science, art, cultivated intelligence, with all the outward elegancies of life, will not save our beloved country from threatened moral and social failure. Nothing will do this but Christian homes where reigns the harmony which is found in the good & perfect will of God.”

James E. Rhoads, Inaugural Address for Bryn Mawr College, 1885

Only the mother is physically present in this family scene, supervising her children as they entertain themselves with balls and bubbles. She is relaxed, even drowsy, resting her head in her hand and her feet on a footstool. The father, in contrast, is presumably working outside the home. Nevertheless, his watchful presence is still as he gazes from an elaborately framed portrait the wall. Taylor, Rhoads, and the Board of Trustees all envisioned women at Bryn Mawr one day taking a similar place within the private sphere.

“The Laundry and Boiler House has been roofed and plastered…The building is a very plain one, but not more so than its uses justify, and when covered in vines it will not detract from the pleasing appearance of the buildings as a group.”

-Annual Report of Bryn Mawr College, 1884,” Bryn Mawr College Board of Trustees Meeting Minutes, October 10, 1884, Special Collections, Bryn Mawr College

While the residential halls were built on a grand scale, functional buildings like the Laundry and Boiler House, were small-scale, brick constructions in simple styles. The Trustees ensured that functional buildings did not interfere with the aesthetics of the campus. Ivy was grown to cover brick facades.

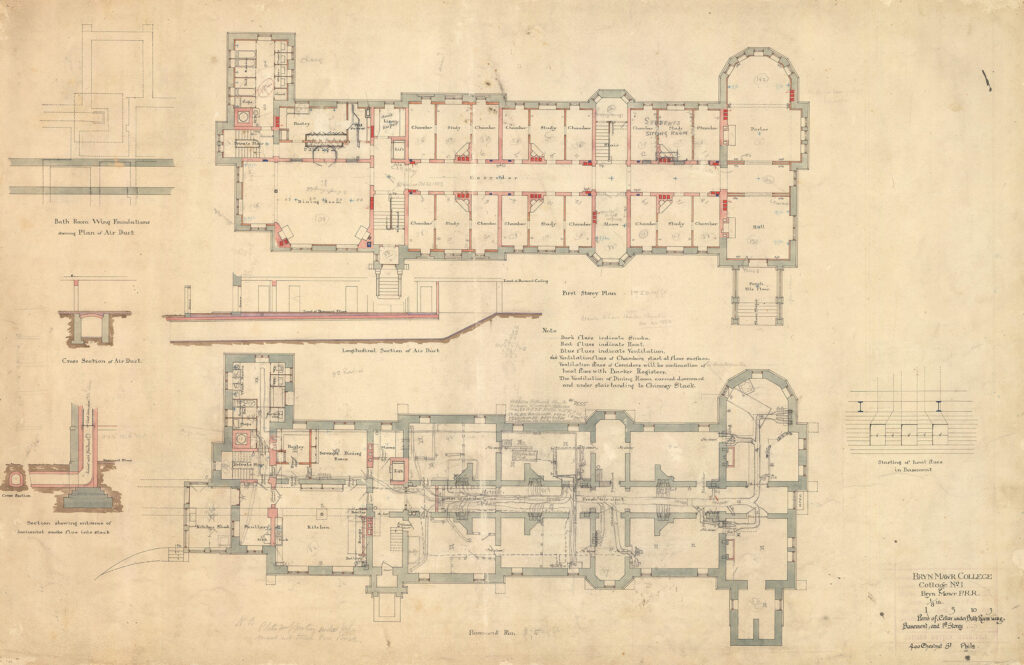

As the transmission of airborne illness became better understood in the nineteenth century, ventilation became a major concern in architectural design. This plan of the basement of Merion Hall displays hand-drawn notes projecting air flow through the building. The annotations reveal the provisional, projective, and working nature of these architectural drawings. Hidden from students in the basement, Merion’s mechanical operations were placed adjacent to service areas including the cellar, kitchen, and staff dining room. This design spatially elided building mechanicals and service staff.

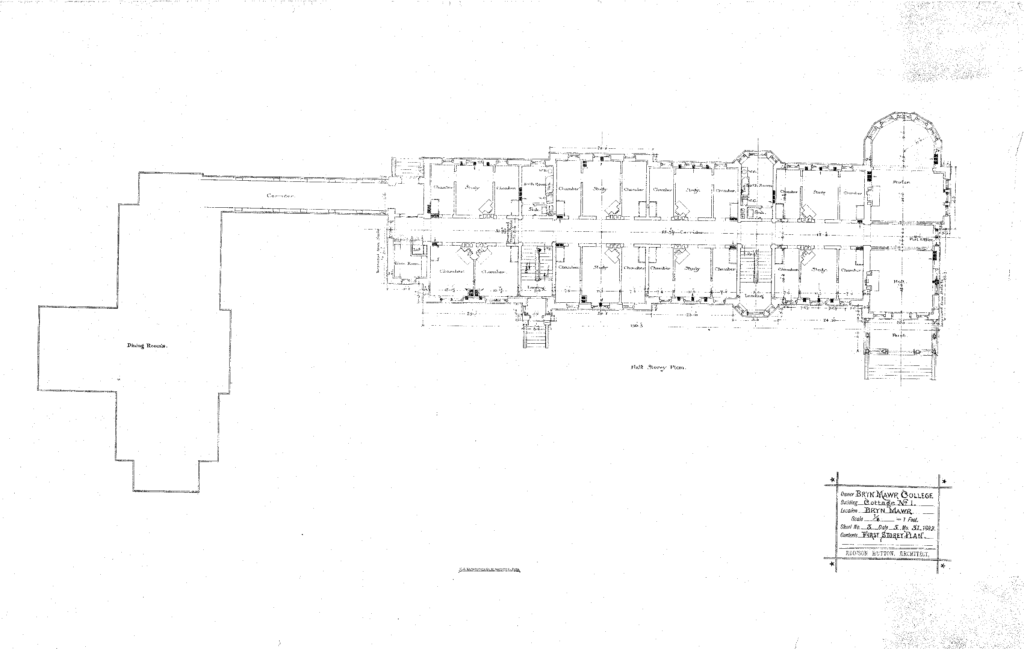

Cottage No. 1: Plans of Cellar under Bathroom Wing,

Basement and 1st Storey, October 3, 1883

Ink on paper

Bryn Mawr Facilities Services

“Under no circumstances are servants permitted to do laundry work for students. Students who wish to employ washerwomen in Bryn Mawr must submit the names of these women to the Mistress of their hall for approval, and only such washerwomen will be approved as comply with the regulations of the College. The wash must be called for and returned within two hours on the two days of the week appointed by the Mistress of each hall as the days for fetching and bringing back the wash; students whose wash is not ready at the appointed hour on the appointed day must therefore wait to send their wash, or to receive it, until the same day of the following week. All washerwomen must use the kitchen entrance on the outside roads.”

Radnor Dorm Rules, from the scrapbook of Bertha Szold (Levin) (class of 1895), Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, BMC-9LS-SCP20

This lengthy rule about laundry in Radnor Hall may have protected staff from student exploitation, but it also demonstrates the strict regulation of contact between students and service workers. It stipulates that washerwomen may not use the front entrance, ensuring that the physical labor required to run College life was less visible. The segregation of domestic staff from students produced and secured class distinctions.

The buildings on campus dedicated to student use were decorative and grand, intended to communicate the “higher and more refined class” of the students. In the elevation drawing for Merion Hall, Hutton designed elaborate horizontal bands above windows, elegant chimneys, and crenellation above the oriel bay window.

An early plan and elevation drawing for Merion Hall indicates a passageway connecting it to the economic building or Annex, where service staff lodgings and labor were isolated. Hutton did not draft the elevation of the Annex. The lesser concern he afforded to this building is also apparent in the plan, which renders its interior as a void, with details to be determined later.