It is perhaps ironic that one of the earliest proposals for Bryn Mawr College was written by a woman whose name our community has largely forgotten. During a period when the College was predominantly discussed in letters exchanged between middle-aged men, a twelve-page printed essay by a twenty-something woman stands out as an intriguing anomaly— yet it has remained relatively unknown and unrecognized. This woman, Elizabeth T. King (1858-1914), crafted a plan outlining her ideas for Bryn Mawr College in 1879, six years before the College opened in 1885.

H.S. Squyer, “Bessie T. King”, undated, photograph, Bryn Mawr College Special Collections,

PA_King_Bessie_003; BMC-Photo Archives, Series I, PA Series: People, T-5: Thomas, M. Carey (2 of 2).

Elizabeth, known as “Bessie,” began writing her paper, Suggestions for the Organization of the Proposed Female College at Bryn Mawr, PA (referred to here as Suggestions), in December 1878.1 She focused on the student experience, organized into subsections including admissions, academics, professional training, physical education, discipline, and the necessary campus buildings. According to her, the need for such an institution was three-fold: to provide female students “more institutions where the work they do will be effectual, where they can systematically labor under excellent instructors, and where the results of their study will give them a recognized, definite position from which to start in life.”2 In response to the concern that the College would not attract a sufficient number of students, Bessie outlined the need to accommodate both students who wished to explore the curriculum in a general course of study and those who were coming to the College with specific, professional ambitions in mind. She recognized that “while it is highly desirable that all who have the means should first obtain general culture, yet, at present, it is the women whom necessity is sending into a profession, who chiefly go to college, and secondarily for more affluent women interested in broadening their intellectual horizons. They are forced to get the training, while women of leisure do not feel the same spur.”3 In other words, while Bessie acknowledged the value of a college where intellectually curious women could explore ideas, she saw Bryn Mawr as primarily attracting students who sought professional training to provide for themselves financially.

Bessie was the daughter of Francis T. King (1819-1891), a prominent Orthodox Quaker businessman from Baltimore. The founder of Bryn Mawr College, Joseph Wright Taylor (1810-1880), appointed Francis as the first President of Bryn Mawr’s Board of Trustees in 1877. In a letter to Joseph dated December 1878, Francis asserts “entre nous for Bessie’s own benefit, I asked her to write out her views from the student standpoint which she finally agreed to do if no one saw it but her, myself and her sisters” (underlining original to letter). According to her father, Bessie’s Suggestions was initially a private endeavor, one he took credit for encouraging. Despite Bessie’s stipulations, Francis did share her writing. Only two sentences later Francis tells Joseph, “If I am as well pleased with [Bessie’s paper] when finished I will let thee see it, when thee comes down to [Baltimore].”4 Francis eventually showed the letter not only to Joseph, but also to a number of other influential Quaker men, including several future members of the Bryn Mawr Board of Trustees— James E. Rhoads, John B. Garrett, Edward Bettle Jr., and James P. Whitall. Bessie’s perspective was purportedly well received; according to Francis’s correspondence with Joseph, all these individuals “[used] strong commendatory language” when discussing Bessie’s paper.5

An Indirect Collaborator

From these letters it is clear that Bessie’s Suggestions was distributed to — and appreciated by — numerous individuals who were directly involved in the creation of Bryn Mawr. As a result, we can speculate that Bessie’s writing may have influenced the formation of the College. There are clear similarities between early College materials — including Minutes of the Board of Trustees, Minutes of the Executive Committee, and College Programs — and Bessie’s Suggestions. For instance, both Bessie’s Suggestions and the Board of Trustees articulated the ambition “to give [students] a thorough and generous intellectual culture.”6 To accommodate students from less affluent backgrounds, Bessie advocated for the creation of scholarships for students within the Society of Friends.7 The Minutes of Board of Trustees reflect that in June 1884, this came into effect.8 Likewise, Bessie prioritized the teaching of chemistry, physics, and biology within the College’s science curriculum and the importance of English, German, and French within the modern languages.9 The minutes of an October 1884 Board of Trustees meeting reflects a similar emphasis on these subjects. Such details do not prove Bessie’s influence, yet the similarities are compelling. Neither Bessie’s name, nor her paper is ever cited in official College documents, however, this is not surprising, as these sources do not frequently attribute ideas to specific members of the College administration, let alone outside individuals.

There are also key places where Bessie’s Suggestions and the College’s early administrative records differ. Bessie advocated for placing the dining hall and other practical facilities in a separate building from student dormitories. She imagined that this building would contain “all the economic departments of the college… the cellar, the heating apparatus for this and the academic building; on the first floor, the dining hall, china and grocery closets and kitchen; and on the second floor, over the dining room, the sitting and lodging room for servants, and over the kitchen, the laundry.”10 The placement of the kitchen and dining hall was extensively debated. While Joseph Taylor and the Board of Trustees initially shared Bessie’s viewpoint, by 1882 the Trustees decided to place the dining room, kitchen, and other facilities within Merion Hall in order to reduce expense.11 Although we do not know for certain that Bessie’s Suggestions were taken into account by the first Board, the parallels between her work and the College’s early institutional publications highlight her role as a potential collaborator with the men who were more directly involved in the formation of the College.

There are also strong thematic differences between the documents, such as Bessie’s focus on student life after Bryn Mawr versus the more practical concerns of the College’s records. As seen in the “Special Callings” section of Suggestions, Bessie emphasized how higher education for women was connected to the professional opportunities available to them — in fields ranging from medicine to theological ministry to design.12 In contrast, the Trustees emphasized that the College was meant “to develop womanly character, to fit its students to enjoy life more fully… whether in the home, in social, or religious life, or in any of those varied occupations in which women of education now engage.”13 Though this final clause does refer to the professional roles potentially available to women, it is presented as just one of several possible pathways for women after graduation from Bryn Mawr, rather than a central impetus for attending. Indeed, the Board of Trustees never adopted professional preparation as a broad goal of the institution, a decision that might have been dictated by Taylor’s will, which stipulated teaching as the only anticipated occupation of Bryn Mawr graduates.14

But why would Bessie have reason to write her Suggestions in the first place? What informed her opinions on the College? And how can we understand her role within Bryn Mawr’s history? To answer these questions, we must examine Bessie herself.

Beginnings: A Woman Shaped by Connections and Convictions

Elizabeth “Bessie” T. King (who was later known by her married name, Elizabeth King Ellicott) was born in 1858 to a wealthy Orthodox Quaker family in Baltimore. Her father, Francis T. King, a prominent businessman, was on the boards of several institutions of higher education: Johns Hopkins University, Haverford College, and later Bryn Mawr College.15

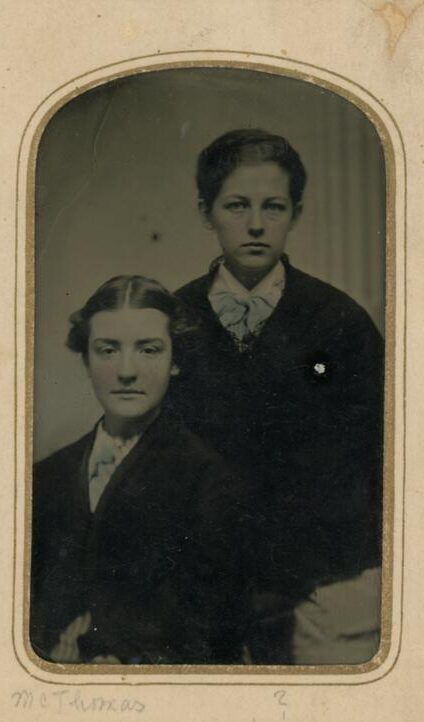

As a young girl, Bessie was very close with her cousin, M. Carey Thomas. Both girls grew up in Baltimore and they shared a mutual sense of curiosity and ambition. They were good friends throughout their childhoods and together attended Howland Institute, a Quaker boarding school for young women in Ithaca, New York.16 A picture dating to around 1875 shows them dressed in men’s clothing for a costume party they hosted while at Howland, highlighting their mutual interest in pushing the limits of what was expected of women in the period.17 Over the course of their friendship, they also shared a subtle divergence from their religious upbringings. Thomas notably deviated from Quakerism during her college years, and in Bessie’s correspondence to her cousin she frequently referred to her disinterest in the religion. In an 1880 letter, Bessie writes of staying home from the Sunday service and enjoying “all the quiet of our Friends meetings with none of the drawbacks.”18

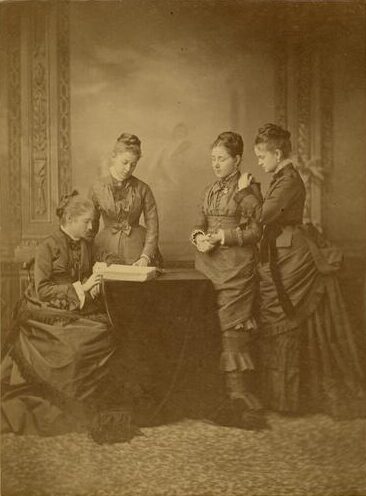

In 1877, Bessie introduced M. Carey Thomas and her friend Mary “Mamie” Mackall Gwinn to two young women from Bessie’s elite Baltimore neighborhood: Mary Garrett and Julia Rogers.19 The five young women formed a strong bond and named themselves the Friday Evening Group. They remained close friends for the next fifteen years. They collaborated to found the Bryn Mawr School in Baltimore, which opened in 1885 and acted as a feeder school for Bryn Mawr College. In 1889, they raised substantial funds for Johns Hopkins Medical School, with the condition that it open with admission for both sexes.20 M. Carey Thomas became Bryn Mawr College’s first Dean of the Faculty and second President, while Mamie Gwinn was one of the College’s first English professors. Mary Garrett bankrolled the College for nearly thirty years. Julia Rogers, the one member of the group not immediately connected to Bryn Mawr College, was instrumental in the development of the Women’s College of Baltimore (now Goucher College) and bequeathed the majority of her fortune to that institution.21

J. H. (John Henry) Pope, “M. Carey Thomas and Bessie King” (c. 1875), photograph, Bryn Mary College Special Collections, https://digitalcollections.tricolib.brynmawr.edu/object/bmc8003

Norval H. Busey, “M. Carey Thomas, Mary Garrett, Julia Rogers, Mamie Gwinn, Bessie King” (July 1879), photograph, Bryn Mary College Special Collections, https://digitalcollections.tricolib.brynmawr.edu/object/bmc8009

Bessie herself was quite ambitious. In 1876 she applied to Johns Hopkins University but did not end up attending.22 This is surprising given Francis T. King’s involvement in higher education (including his membership on the Board of Trustees of Johns Hopkins) but may have been the result of Bessie’s standing as a member of an elite social stratum. Bessie herself asserted in her Suggestions that “women of leisure” did not have the same need for a college education as women of lower socio-economic status, who were obligated to support themselves financially.23 M. Carey Thomas’ family was less affluent than the Kings. She began attending Cornell University in 1875 (graduating in 1877) and studied briefly at Johns Hopkins University (where her father, James Carey Thomas, was also on the Board) before seeking an education in Europe— first in Germany, and then in Switzerland from 1879-1882—earning her doctorate from the University of Zurich. It was not necessary for Bessie to secure future prospects through higher education in the same way required of M. Carey Thomas.

Furthermore, while both Bessie King and M. Carey Thomas were ambitious women, it is possible that Bessie was less assertive than her cousin. Bessie may have been more easily swayed by the opinions of her father, especially given the fact that her mother passed away when she was a child. In contrast, M. Carey Thomas’s strong-willed mother (Mary Whitall Thomas) and aunt (Hannah Whitall Smith) encouraged Thomas to pursue opportunities aggressively. A comparison of correspondence from Bessie and M. Carey Thomas reveals this distinction. In a January 1879 letter to Joseph Taylor concerning her Suggestions, Bessie modestly admits “I feel [my paper] can be necessarily of little value except as an expression of my continued interest in the great work for which thee will have the gratitude of all the women in our society.”24 In contrast, in 1883 M. Carey Thomas wrote to James Rhoads, who was by then established as an important member of Bryn Mawr’s Board of Trustees, confidently proposing herself as the President of the new college. This was only a year after M. Carey Thomas had received her Ph.D. summa cum laude, when she was only twenty-six years old.25

Yet, despite these initial hurdles and differences in character, Bessie remained committed to her progressive convictions and pushed against heteronormative gender expectations. According to M. Carey Thomas, when Bessie was in her early twenties, Bessie told her that she thought one should only marry in middle age so as to have a companion (and presumably to avoid having children in an era before reliable contraception).26 The pressures and constraints of marriage and child rearing were concerns shared among members of the Friday Evening Group, most of whom never married. Bessie followed through on her beliefs and did not marry until 1900, when she was in her early forties.27 In her fourteen years of marriage, she never had children.

A Shift Towards Active Influence and the Professional World

Bessie’s firm belief in the importance of professional preparation for women emerged as a major concern in her subsequent commentaries. She submitted a paper for the 1880 Conference on Education in the Society of Friends titled “The Professional Side of Women’s Education.”28 In this piece she thoroughly laid out the professional opportunities available to women at the time, and how a college education would equip them for those fields. In other words, she was not concerned with breaking glass ceilings, but with helping women pursue the career paths that were already available to them. Eight other women at the 1880 conference shared opinions about the formation of Bryn Mawr, yet they, too, typically go unacknowledged as contributors to Bryn Mawr’s founding.29 Although a number of these women mentioned opportunities that a college education could provide outside of the domestic sphere, Bessie’s piece was unique in the degree to which she stressed professionalism.30

Unknown photographer, “Mary Elizabeth Garrett, Bessie King, and others” (1880), photograph, Bryn Mary College Special Collections https://digitalcollections.tricolib.brynmawr.edu/object/bmc8099

M. Carey Thomas was studying in Switzerland at the time of the 1880 conference, and therefore was not a part of these conversations. However, Bessie kept her cousin thoroughly appraised of developments and even encouraged her to apply for a position within the College. In a letter from January 1880, she plants the idea of involvement in the College, writing “I really think we may look forward to being able to be useful there…Do think of it.”31 Later, in a letter dated May 1881, Bessie advises Thomas on taking on a professorship at the College, in which she states, “I hope thee will write to both thy father [James Carey Thomas] & Uncle James [Whitall] and let me read parts of thy letters to me to father [Francis T. King]” — all of these male relatives were on Bryn Mawr’s Board of Trustees.32 Finally, in a letter from the summer of 1883, Bessie tells her cousin “thee has done well in writing to Dr. Rhoads” (undoubtedly referring to Thomas’s letter proposing herself as President of the College, written in 1883), and “if thee takes the position [as President] I do not think thee need to feel radically at variance & a little patience will be all that is needed [when dealing with the Trustees].”33 From these letters Bessie’s indirect influence on the College is clearly apparent. While she herself was never officially affiliated with the College, this correspondence reveals how she pulled strings behind the scenes and acted as a middle (wo)man between her father and cousin.

Alongside the successful collaborations of the Friday Evening Group were a series of tensions. A debate over the admission of a Jewish student to the Bryn Mawr School in 1886 divided them, with Bessie, Mary Garrett, and Julia Rogers supporting her admission and M. Carey Thomas and Mamie Gwinn strongly opposing.34 Questions about the running of the Johns Hopkins Medical School caused friction. Subtle but longstanding animosity between Bessie, Mary Garrett, and Julia Rogers (evident in Bessie’s letters) culminated in the group disbanding in 1893.35 It is significant that this falling out happened only after Francis T. King’s passing in 1891. M. Carey Thomas may have preserved her personal relationship with Bessie to benefit her professional relationship with Bessie’s father, who remained the President of the Board of Trustees until his death.36

Power, Privilege, and Exclusion

As the daughter of Francis T. King, Bessie participated in an elite social circle of Orthodox Quakers that included Bryn Mawr’s founder and members of the Board of Trustees. She was automatically in a position of privilege and access within this community. She also benefited from substantial generational wealth. According to census records from 1870, Bessie’s household consisted of her widowed father, two elder sisters, her paternal uncle, and her grandparents.37 The census records also note three domestic staff residing in the King home. Sarah Whittington, a white woman in her fifties identified in the census as a chamber maid, and Eliza Stewart, a black woman in her forties described as a cook, had both been with the King family household for at least ten years.38 The final staff member was John Helren, a black man in his twenties, who worked for them as a waiter. These details highlight the privileged home environment to which Bessie was accustomed throughout her life. In Francis T. King’s will, Bessie received $20,000 (over $600,000 today), plus an additional sum of his estate that was divided between Bessie and her two sisters.39

In the 1890s, Bessie turned her attention to the Maryland women’s suffrage movement. The Equal Suffrage League, headed by Bessie, submitted a bill to the Maryland State legislature in 1910, but it was not passed.40 Bessie brought the bill forward again in 1912 and 1914, but it was again voted down. This bill and Bessie’s papers on women’s education speak to how she used her writing to try to enact change. However, her progressive views had limitations and were bound up with Bessie’s own social privilege, elitism, and racism. The bills that Bessie helped submit would have disenfranchised poor and illiterate voters. It stated that all residents of Baltimore age twenty-one or older, regardless of gender, would have the right to vote, provided that they

possess any one of the following qualifications, to wit: (a) If such person is qualified to vote for members of the House of Delegates; or (b) if he or she can read or write, from dictation, any paragraph or sentence of more than five lines contained in the Constitution of Maryland; or (c) if he or she is assessed with property in said city to the amount of $300 and has paid taxes thereon for at least two years preceding the election at which he or she offers to vote.41

The bill ostensibly opened the vote to women of any race, and some Maryland legislators opposed it because they decried its equation of Black and white women, which they believed would incite social unrest.42 Yet stipulations regarding educational level and economic standing would have barred most Black people in post-Reconstruction America, who historically did not have access to these resources. While Bessie’s bill may signify activism for women’s suffrage, it also attempted to codify white supremacy.43

A Baltimore newspaper of the period, The Afro-American Ledger, featured an article in March 1909 arguing against a similarly structured suffrage amendment proposed for the November 2, 1909 ballot.44 A quoted statement from the Negro Suffrage League explained

This proposed amendment…and its main purpose is to disfranchise the Negro voters of this state because they are Negroes… if it becomes the law of the state, be so applied as to make the colored people more dependent and subjects of greater persecution than we now have to endure…. Therefore we protest against this proposed amendment, which we believe has for its intent to deprive the colored people of Maryland of civil and political liberty and to close the door of hope against us as a race.45

The 1909 bill was unsuccessful but may have inspired the legislation that Bessie helped promote. Furthermore, the Maryland women’s suffrage movement, in which Bessie played a substantial role, was starkly segregated, forcing Black women like Augusta T. Chissell to create their own suffrage leagues.46 Chissell was involved in several Black women’s organizations in Baltimore, including the Progressive Women’s Suffrage Club, founded by Estelle Hall Young in 1915.47

In her will, Bessie made a substantial bequest of a fund to support the Black community of Maryland, which was celebrated in the African American press.48 Yet it is telling that this support did not extend to advocacy for equal suffrage. Her philanthropy and activism were racially distinct, meaning that her efforts to benefit the Black community did not challenge white supremacy and power.

These biographical details of Bessie’s life exemplify the complexity and contradiction within her character. Her progressivism and prejudices both strongly influenced her Suggestions, which represented a vision of opportunities for women — but a very particular set of women, who were white, educated, predominantly Christian, and of the middle- and upper-classes. Bessie’s Suggestions have been long overlooked within our narratives of Bryn Mawr, despite the possibility that they influenced early decision making about the College’s development. Still, there is a reason Bessie’s name is unfamiliar to our community. Her contributions were indirect because of the patriarchal organization of the College administration. After the 1880 educational conference, there were few seats at the table for women to take part in the official decision-making processes. M. Carey Thomas was the exception.

The ramifications of archival silences like that surrounding Bessie King persist today in the way that archives — including those at Bryn Mawr and Haverford — are organized, catalogued, and publicized. Aside from a single letter Bessie King wrote to Joseph Taylor and several dozen to M. Carey Thomas, there are very few records of her connection to the College across the Bryn Mawr and Haverford archives. In fact, the several copies of her Suggestions within the holdings of Bryn Mawr College Special Collections are housed in an unmarked file within a box labeled simply “History.” It contains miscellaneous memorabilia and ephemera from across the College’s history.49 Contrary to popular perception, M. Carey Thomas was not solely responsible for the creation of the College, nor was she the only individual connected to the school’s beginnings to harbor (and act upon) harmful, prejudiced, and exclusionary beliefs. Examining and shedding light on contradictory and problematic figures like Bessie King is an important step in grappling with our institutional history and recognizing the ways its effects still resonate today.

Esmé Read (‘22) researched Elizabeth “Bessie” King as a final project for the spring 2022 course “Telling Bryn Mawr Histories.” She expanded her research through a summer 2022 Research Assistantship in Special Collections.

Suggested Reading

Primary Sources

Bryn Mawr College. College Program 1885-1886. 1885.

Bryn Mawr College. College Program 1886-1887. 1886.

Bryn Mawr College Board of Trustees, Minutes of the Trustees of Bryn Mawr College, Volume 1, 1880-1885, Archives 2B 1A1-1A2, Bryn Mawr (Board Meeting Minutes), Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

Bryn Mawr College Executive Committee, Executive Committee Minutes, 1884-1894, Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

Ellicott, Elizabeth T. King. Letters to M. Carey Thomas, 1870-1890, Series I, Reel 39, M. Carey Thomas Papers, Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

Equal Suffrage League of Baltimore, “Leaflet: The Equal Suffrage League of Baltimore. Proposed amendment to the Baltimore City Charter. [Circa 1909-1910],” Ann Lewis Women’s Suffrage Collection, https://lewissuffragecollection.omeka.net/items/show/1580, accessed 30 August 3022.

King, Elizabeth T. Suggestions for the Organization of the Proposed Female College at Bryn Mawr, PA. 1879.

King, Francis T. Letters to Joseph Taylor, 1878-1879, HC.MC-962, Box 3, Taylor Family Papers, Haverford College Quaker and Special Collections, Haverford, PA.

King, Francis T. Will dated 28 October 1891, Pennsylvania, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1683-1993 – AncestryLibrary.Com.” Accessed 9 April 2022. https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/discoveryui-content/view/2334690:8802?tid=&pid=&queryId=dcce5febf878642a83249a885cfe9153&_phsrc=LEQ2&_phstart=successSource.

“The Late Mrs. Ellicott.” The Afro-American Ledger, 24 May 1914.

“Maryland Elective Franchise, Amendment 1 (1909),” https://ballotpedia.org/Maryland_Elective_Franchise,_Amendment_1_(1909)#cite_note-1, accessed 30 August 2022.

“Negro Voters Active: Suffrage League at Baltimore Will Fight Disfranchising Amendment.” The Afro-American Ledger. 27 March 1909. https://news.google.com/newspapers/p/afro?nid=UBnQDr5gPskC&dat=19090327&printsec=frontpage&hl=en,

Proceedings of a Conference on Education in the Society of Friends, Held at Haverford College, Penn., Seventh Month 6th and 7th, 1880. Philadelphia: J. H. Culbertson & Co., Printers, 1880.

Secondary Sources

Archives of Maryland (Biographical Series), “Elizabeth King Ellicott (1858-1914). MSA SC 3520-13588,” Maryland State Archives website, https://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc3500/sc3520/013500/013588/html/13588bio.html, accessed 9 April 2022.

“Baltimore’s African American Suffragists · Hopkins and the 19th Amendment: Activists in Suffrage and Health Reform. Exhibits: The Sheridan Libraries and Museums,” https://exhibits.library.jhu.edu/exhibits/show/hopkins19thamendment/mobilizingbaltimore/africanamericansuffragists, accessed 24 August 2022.

“Biographical Sketch of Elizabeth King Ellicott | Alexander Street Documents.” https://documents.alexanderstreet.com/d/1010596272, accessed 7 May 2022.

“Biographical Sketch of Estelle Hall Young | Alexander Street, Part of Clarivate,” https://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/bibliographic_entity%7Cbibliographic_details%7C4384803/biographical-sketch-estelle-hall-young#page/1/mode/1/chapter/bibliographic_entity|bibliographic_details|438480, accessed 24 August 2022.

“Biographies – Augusta T. Chissell,” https://msa.maryland.gov/msa/educ/exhibits/womenshallfame/html/chissell.html#top, accessed 24 August 2022.

The Bryn Mawr School, Baltimore, “The Bryn Mawr School. History,” https://www.brynmawrschool.org/about/history, accessed 29 August 2022.

Goucher College, “Julia Rebecca Rogers. The Name Behind the Legacy…,” https://www.goucher.edu/library/special-collections-and-archives/exhibits/building-a-greater-goucher-the-history-of-the-towson-campus/honored-individuals/julia-rebecca-rogers, accessed 30 August 2022.

Hamilton, Andrea. A Vision for Girls: Gender, Education, and the Bryn Mawr School. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004.

Horowitz, Helen Lefkowitz. The Power and Passion of M. Carey Thomas. 1st ed. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1994.

Hruban, Claire. “The Bryn Mawr School and the Suffrage Movement,” blog post in Bryn Mawr Recollected: Stories from the History of the Bryn Mawr School, 2 September 2020. https://brynmawrrecollected.wordpress.com/, accessed 9 April 2022.

Pumroy, Eric. “Bryn Mawr.” In Founded by Friends: The Quaker Heritage of Fifteen American Colleges and Universities, edited by John W. Oliver Jr., Charles L. Cherry, and Caroline L. Cherry, pp. 147-62. Lanham, MD: The Scarecrow Press, 2007.

Sander, Kathleen Waters. Mary Elizabeth Garrett: Society and Philanthropy in the Gilded Age. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008.

Wallace, Mal Hee Son. “Elizabeth King Ellicott, 1858-1914: Suffrage and Civic Leader.” In Notable Maryland Women, edited by Winifred G. Helmes, pp. 116-22 (Cambridge: Tidewater Publishers, 1977).

Notes

1 Elizabeth T. King, “Suggestions for the Organization of the Proposed Female College at Bryn Mawr, Pa.,” n.d.

2 Elizabeth T. King, Suggestions for the Organization of the Proposed Female College at Bryn Mawr, PA. (1879), 1.

3 King, Suggestions, 3.

4 Francis T. King, letter to Joseph Taylor, 15 December 1878, Taylor Family Papers, HC.MC-962, Box 3, Haverford College Quaker and Special Collections, Haverford, PA.

5 Francis T. King, letter to Joseph Taylor, 4 March 1879, Taylor Family Papers, HC.MC-962, Box 3, Haverford College Quaker and Special Collections, Haverford, PA.

6 Bryn Mawr College Board of Trustees, Minutes of the Trustees of Bryn Mawr College, 1880-1885, November 1883, volume 1, 85, Archives 2B 1A1-1A2, Bryn Mawr (Board Meeting Minutes), Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA. Bessie articulated this same goal as follows: “It [Bryn Mawr] can offer as of first importance, a place where women will be able to train their minds so well that, after leaving college, they will continue their education under different conditions of life.” King, Suggestions, 1.

7 King, Suggestions, 2.

8 Bryn Mawr College Board of Trustees, Minutes of the Trustees of Bryn Mawr College, 1880-1885, 19 June 1884, volume 1, 105, Archives 2B 1A1-1A2, Bryn Mawr (Board Meeting Minutes), Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

9 King, Suggestions, 2, 4-5.

10 King, Suggestions, 11-12.

11 Bryn Mawr College Board of Trustees, Minutes of the Trustees of Bryn Mawr College, 1880-1885, 24 November 1882, volume 1, 67, Archives 2B 1A1-1A2, Bryn Mawr (Board Meeting Minutes), Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

12 King, Suggestions, 7-8.

13 Bryn Mawr College Board of Trustees, Minutes of the Trustees of Bryn Mawr College, 1880-1885, November 1883, volume 1, 85, Archives 2B 1A1-1A2, Bryn Mawr (Board Meeting Minutes), Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

14 Will (with codicil) of Joseph Wright Taylor (certified copy), c. 1870-1880. Taylor Family Papers, HC.MC-962, Box 7, Folder 9, Haverford College Quaker and Special Collections, Haverford, PA.

15 Archives of Maryland (Biographical Series), “Elizabeth King Ellicott (1858-1914). MSA SC 3520-13588,” Maryland State Archives website, https://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc3500/sc3520/013500/013588/html/13588bio.html.

16 Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz, The Power and Passion of M. Carey Thomas, 1st ed. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1994), 37.

17 Horowitz, The Power and Passion of M. Carey Thomas, 43.

18 Elizabeth King Ellicott, letter to M. Carey Thomas, 11 July 1880, M. Carey Thomas Papers, Series I, Reel 39, Bryn Mawr College Special Collections.

19 Kathleen Waters Sander, Mary Elizabeth Garrett: Society and Philanthropy in the Gilded Age (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008), 78.

20 The Bryn Mawr School, Baltimore, “The Bryn Mawr School. History,” https://www.brynmawrschool.org/about/history.

21 For a summary of Julia Roger’s life and achievements, see Goucher College, “Julia Rebecca Rogers. The Name Behind the Legacy…,” https://www.goucher.edu/library/special-collections-and-archives/exhibits/building-a-greater-goucher-the-history-of-the-towson-campus/honored-individuals/julia-rebecca-rogers.

22 Sander, Mary Elizabeth Garrett, 78.

23 King, Suggestions, 3

24 Elizabeth King Ellicott, letter to Joseph Taylor, 27 January 1879, Taylor Family Papers, HC.MC-962, Box 3, Haverford College Quaker and Special Collections, Haverford, PA.

25 Eric Pumroy, “Bryn Mawr,” in Founded by Friends: The Quaker Heritage of Fifteen American Colleges and Universities, edited by John W. Oliver Jr., Charles L. Cherry, and Caroline L. Cherry, pp. 147-62 (Lanham, MD: The Scarecrow Press, 2007), 151.

26 Horowitz, The Power and Passion of M. Carey Thomas, 130.

27 “Biographical Sketch of Elizabeth King Ellicott | Alexander Street Documents,” https://documents.alexanderstreet.com/d/1010596272.

28 Proceedings of a Conference on Education in the Society of Friends, Held at Haverford College, Penn., Seventh Month 6th and 7th, 1880 (Philadelphia: J. H. Culbertson & Co., Printers, 1880), 99–107.

29 These women include Mary Whitall Thomas (mother of M. Carey Thomas, wife of Board of Trustee Member James Carey Thomas, and sister of Board of Trustee Member James Whitall); Mary Rhoads Haines (sister of Board of Trustee Member [and later President] James Rhoads and mother-in-law of Board of Trustee Member John B. Garrett); Annie E. Johnson (Principal of Bradford Academy, Bradford MA); Mary Anna Longstreth (founder of a Quaker girls school, of Philadelphia); Ruth Murray (of New York); Elizabth Comstock (a Quaker minister and social reformer, of Ohio); Rhoada Coffin (wife of Charles F. Coffin, of Indiana); and Hannah Bean (a Quaker minister, of Iowa).

30 Proceedings of a Conference, 24–27; 91-107.

31 Elizabeth King Ellicott, letter to M. Carey Thomas, 25 January 1880, M. Carey Thomas Papers, Series I, Reel 39, Bryn Mawr College Special Collections.

32 Elizabeth King Ellicott; letter to M. Carey Thomas; 17, 23 May 1881; M. Carey Thomas Papers; Series I; Reel 39; Bryn Mawr College Special Collections.

33 Elizabeth King Ellicott; letter to M. Carey Thomas; 3 June, 1 July 1883; M. Carey Thomas Papers; Series I; Reel 39; Bryn Mawr College Special Collections.

34 Horowitz, The Power and Passion of M. Carey Thomas, 230–32; Andrea Hamilton, A Vision for Girls: Gender, Education, and the Bryn Mawr School (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004), pp. 40-41.

35 Elizabeth King Ellicott, letter to M. Carey Thomas, 19 March 1882, 14-25 May 1882, 21 July 1882, 17 January 1883, 23 April 1883, M. Carey Thomas Papers, Series I, Reel 39, Bryn Mawr College Special Collections. Also see Horowitz, The Power and Passion of M. Carey Thomas, 228–30; Sander, Mary Elizabeth Garrett, 130, 175.

36 Horowitz, The Power and Passion of M. Carey Thomas, 237–38.

37 “1870 United States Federal Census,” AncestryLibrary, accessed August 31, 2022, https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/discoveryui-content/view/23289729:7163.

38 “1860 United States Federal Census,” Ancestry Library, accessed August 31, 2022, https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/discoveryui-content/view/53561501:7667.

39 “Will of Francis T. King; Pennsylvania, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1683-1993,” Ancestry Library, accessed August 31, 2022, https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/discoveryui-content/view/2334690:8802?tid=&pid=&queryId=dcce5febf878642a83249a885cfe9153&_phsrc=LEQ2&_phstart=successSource.

40 Archives of Maryland (Biographical Series), “Elizabeth King Ellicott (1858-1914). MSA SC 3520-13588,” Maryland State Archives website, https://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc3500/sc3520/013500/013588/html/13588bio.html.

41 Equal Suffrage League of Baltimore, “Leaflet: The Equal Suffrage League of Baltimore. Proposed amendment to the Baltimore City Charter. [Circa 1909-1910],” Ann Lewis Women’s Suffrage Collection, https://lewissuffragecollection.omeka.net/items/show/1580.

42 Mal Hee Son Wallace, “Elizabeth King Ellicott, 1858-1914: Suffrage and Civic Leader,” in Notable Maryland Women, edited by Winifred G. Helmes (Cambridge: Tidewater Publishers, 1977), 119.

43 Claire Hruban, “The Bryn Mawr School and the Suffrage Movement,” blog post in Bryn Mawr Recollected: Stories from the History of the Bryn Mawr School, 2 September 2020, https://brynmawrrecollected.wordpress.com/.

44 “Maryland Elective Franchise, Amendment 1 (1909),” https://ballotpedia.org/Maryland_Elective_Franchise,_Amendment_1_(1909)#cite_note-1.

45 “Negro Voters Active: Suffrage League at Baltimore Will Fight Disfranchising Amendment,” The Afro-American Ledger, 27 March 1909, 6, https://news.google.com/newspapers/p/afro?nid=UBnQDr5gPskC&dat=19090327&printsec=frontpage&hl=en, accessed 30 August 2022; cited in Hruban, “The Bryn Mawr School and the Suffrage Movement.”

46 “Biographies – Augusta T. Chissell,” https://msa.maryland.gov/msa/educ/exhibits/womenshallfame/html/chissell.html#top.

47 “Biographical Sketch of Estelle Hall Young | Alexander Street, Part of Clarivate,” https://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/bibliographic_entity%7Cbibliographic_details%7C4384803/biographical-sketch-estelle-hall-young#page/1/mode/1/chapter/bibliographic_entity|bibliographic_details|4384803; “Baltimore’s African American Suffragists · Hopkins and the 19th Amendment: Activists in Suffrage and Health Reform. Exhibits: The Sheridan Libraries and Museums,” https://exhibits.library.jhu.edu/exhibits/show/hopkins19thamendment/mobilizingbaltimore/africanamericansuffragists.

48 “The Late Mrs. Ellicott.” The Baltimore Afro-American Ledger, 24 May 1914; Archives of Maryland (Biographical Series), “Elizabeth King Ellicott (1858-1914). MSA SC 3520-13588”; Hruban, “The Bryn Mawr School and the Suffrage Movement.”

49 Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, 1H 1879.

It should be noted that Bryn Mawr Special Collections plans to improve the cataloguing description of this box and others in the College archives this coming year as part of the department’s ongoing and thorough reparative work in the collection.