Rhian Muschett (’23) researched Hannah Taylor as a final project for the spring 2022 course “Telling Bryn Mawr Histories.” She expanded her research as a summer 2022 Who Built Bryn Mawr? undergraduate fellow.

In her biography of her great-uncle, the founder of Bryn Mawr College, Joseph Wright Taylor (1810-1880), Margaret Taylor MacIntosh only once directly addresses the subject of Hannah Taylor, Joseph’s sister and arguably his closest companion.[1] Otherwise Hannah appears as a domestic footnote in Joseph’s adventurous life. Hannah never married, and most of her days were dedicated to her brothers and their families, serving as their caretaker and housekeeper. In surveying accounts of Hannah’s life, I sensed that a focus on her domesticity had trivialized the crucial labor she contributed to creating strong bonds across the Taylor family. By maintaining familial cohesion, Hannah not only enriched her siblings’ personal lives, she also contributed to the success of the Taylor family business by preserving a good working relationship among her brothers, who were partners in a lucrative tanning enterprise, which was in turn the source of the fortune that founded Bryn Mawr College. Indeed Charles S. Taylor credited his Aunt Hannah as being “the prime factor in their greatest achievements.”[2] Although the historical record does not suggest that Hannah had any direct role in the founding of Bryn Mawr, her supporting role in Joseph’s life helped make founding the College possible.

My attempt to center Hannah Taylor in the history of Bryn Mawr’s founding was inspired in part by the Colored Conventions Project (CCP). The Colored Conventions were political meetings organized by African Americans from 1830 until after the Civil War to strategize political plans and activism for racial and social justice.[3] The CCP collates and analyzes the minutes of these gatherings, which record the names of Black activists, who are often excluded from modern historical narratives. In an effort to correct the gender imbalance in histories of the American abolition movement, the CCP requires researchers using the database to name an unrecorded woman involved in the conventions for every “official” male member. In this way, the CCP creators actively work to record “those who would otherwise go uncounted and therefore unrecognized for their work.”[4] It must be emphasized, however, that as a white, socio-economically privileged woman, Hannah Taylor’s exclusion from the historical record is in no way equivalent to the erasure experienced by Black female activists of the nineteenth century. The CCP reminds us that the project of identifying marginalized figures in Bryn Mawr’s history must ultimately expand beyond comparatively privileged individuals like Hannah Taylor.

A significant obstacle in naming and contextualizing forgotten historical figures is the gaps in archival records relating to their lives, which make it easy to overlook them. Scholars must therefore intentionally give presence to such absences. Similarly to Hannah, Jane Franklin Mecom, the sister of Benjamin Franklin, is characterized by an “obscurity [that] is matched only by her brother’s fame.”[5] The historian Jill Lepore describes her part-historical, part-biographical account of Mecom’s life as “an allegory: it explains what it means to write history not from what survives, but what is lost.”[6] The remains of Mecom’s letters and papers constitute only a fraction of her known correspondence. Likewise, Hannah Taylor’s archival footprint is primarily composed of a fragmentary collection of letters. In interpreting this material, I do not attempt to fill in archival gaps, implying that the record can be restored. Instead, I aim to represent and question what is now lost and invisible. I use data visualizations to dwell on the silences of Hannah’s archive.

The few secondary accounts of Hannah’s story divide periods of her life according to the male family members with whom she lived, effectively framing her as a femme couvert, a woman under men’s supervision and authority, despite the fact that she never married. In 1912, Charles S. Taylor, Hannah’s nephew and an early member of the Bryn Mawr College Board of Trustees, penned a fifteen-page, unpublished biography of his aunt. He writes that Hannah was born 21 March 1808 in New Jersey, and grew up on the family farm near Imlaystown, Monmouth County. In a letter to Charles, Hannah reveals the date her schooling commenced at Westtown, a Quaker boarding school in West Chester that is still in operation today. Hannah writes “I well remember the day and the date I went as a scholar 12th of 6th mo. /23 [12 June 1823].”[7] Her clear recollection of the date suggests the significance of the event in her life, but she does not provide her personal impression of Westtown, instead asking Charles to “please be candid” about his own experience.[8] Charles writes of Hannah’s education only that “her inclinations did not lead her along the lines of scholarship or scholastic attainment.”[9] Instead, Hannah, like her brothers, “was very observant and possessed more practical knowledge than most of those who gain their learning from books.”[10]

In 1823, Hannah’s parents took up positions as Matron and Superintendent of the Frankford Asylum for the Insane. In 1824-1825, as Hannah’s brother, Abraham Taylor, and cousin, John Bullus, began their tanning enterprise in Ohio,[11] she finished her schooling and then returned home to live with her parents until their deaths in 1832 and 1835.[12] MacIntosh writes that after their father’s death, Hannah’s brothers were “eager to have her join them” in Cincinnati as a “home-maker” to support them and their business.[13] A letter from Joseph dated 15 November 1835 states, “Thee asks in a former letter whether we shall continue housekeeping during next summer… I suppose thee enjoys thyself in the company of thy many friends freed from the toilsome cares of housekeeping which I’ve so often heard thee desire.”[14] Hannah was apparently eager to live with her brothers as a housekeeper, and so joined them in 1836. They shared a household until Abraham’s marriage to Hannah’s close friend, Elizabeth R. Shoemaker, in 1848. Despite the growing importance ascribed to marriage in the nineteenth century, neither Hannah nor Joseph ever married. They lived together beginning in the late 1840’s, eventually moving to Woodlands, their final home in Burlington, New Jersey, in 1854.[15]

Of Hannah’s time in Cincinnati, Charles writes that his “mother’s brother Issac [Shoemaker] was a welcomed inmate of the family a part of the time and I have understood as a suitor for her [Hannah’s] hand,” but his “erratic and uncertain temperament” put an end to the possibility.[16] The novel Married or Single (1857) by Catherine Maria Sedgwick illustrates the difficulty of such situations, especially because married women relinquished their legal rights.[17] Sedgwick aims to direct the American perception of unmarried women away from negative stereotypes found in nineteenth-century American literature.[18] Unlike literary portrayals of unmarried women as “burdensome” or “unsociable loners,” Sedgwick highlights their essential roles in their families, acting as caregivers and housekeepers, or, in some cases, living and working with other single women.[19] In Philadelphia, this variation in household structure was common during the eighteenth century due to the demands of the urban economy and Quaker ideals that afforded women more autonomy.[20] George Fox, the founder of the Society of Friends, envisioned a world in which women and men were equal, as both had access to the “Inner Light of Christ.”[21]

In the nineteenth century, as production was increasingly industrialized, more expendable wealth became accessible, and women of the upper and middle classes gained more leisure time. Middle- and upper-class households were increasingly privatized, which in turn mobilized an ideal of femininity in the 1830’s that came to be known as the “cult of true womanhood.”[22] Prescriptive books and magazines, such as Godey’s Lady’s Book, advertised a model of femininity characterized by “piety, purity, submissiveness and domesticity.”[23] Women’s work in the private sphere was no longer considered to hold a primarily economic value, but instead became an expression of female love, care, and self-sacrifice.[24]

A Portrait of Hannah Taylor

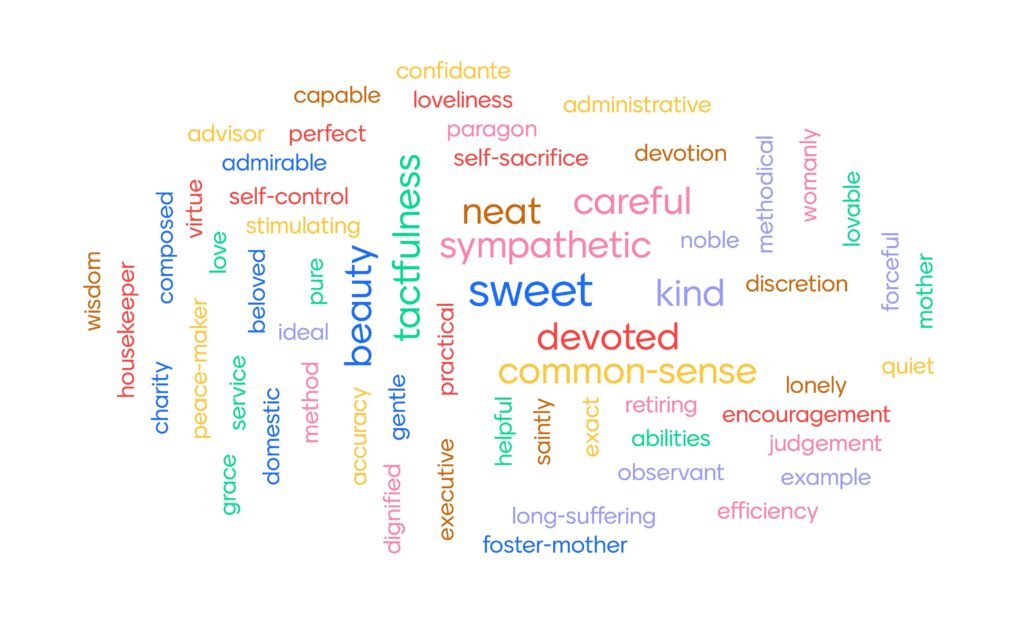

Descriptions of Hannah closely align her with both traditional and newly evolving ideas of femininity by conveying her sympathetic and industrious character. A portrait of Hannah shows her plainly dressed in Quaker style, with a simple cap and unsmiling expression (Figure 1), yet such portraits reveal little of the subject’s personality. To visualize a clearer picture of Hannah’s qualities, I collected modifiers used to describe her from three posthumous accounts: MacIntosh’s biography, Joseph Wright Taylor: Founder of Bryn Mawr College (1936), Charles Taylor’s family history “The Taylor and Shoemaker Families” and his biography of Hannah, “Hannah Taylor, 1808-1889” (Table 1). No letters or contemporaneous papers to or from Hannah were included, as they did not directly describe her. I then used the data to create a word cloud “portrait,” which reflects the frequency of words (and words with shared roots) through relative font size (Figure 2). Hannah is most commonly described as “sweet,” with the words “beauty, tactfulness, neat, careful, sympathetic, kind, devoted and common-sense” also appearing regularly. Altogether, these descriptors paint a picture of a meticulous, practical yet compassionate woman, who embodied the maternal self-sacrifice valued at this time as well as modest pride in her work. Charles writes that he was “taught to look upon my Aunt Hannah Taylor… as a paragon of womanly virtue.”[25] These descriptions of Hannah’s character are not, however, her own words, but instead reflect the impressions of her family and the social ideals of femininity at the time.

Hannah’s internal life—her thoughts, hopes and worries—have not been recorded and will forever remain private. Yet an anonymously authored poem that she kept may provide a small window into her self-perception. Entitled “Humility,” it compares humility to a flower that “does not flaunt its beauties to every vulgar eye” but instead opens “to the sun of righteousness.”[26] This characteristic is evident in her work as a housekeeper. Hannah was recognized by her family for her hard-working spirit and fastidious economy.

Nineteenth Century Domesticity

In a time when “idleness, once a disgrace in the eyes of society, had become a status symbol,” and recognition of economic value of work in the home had been all but erased from the private sphere, housekeeping became paradoxically politicized and moralized.[27] Lydia Maria Child’s The American Frugal Housewife (1829) and Catherine Beecher’s Treatise on Domestic Economy (1841) depict good home life, through well trained housekeeping, as foundational to American identity, and morally influential beyond the home.[28] The American Frugal Housewife specifically engaged its audience with the lower socio-economic classes and reflected Protestant ethics of “honesty, frugality, industry” with which Quaker audiences would have identified.[29] The Quaker ideal of femininity is epitomized by MacIntosh’s description of Hannah as “a model of efficiency and neatness” evident in the gleaming chimneys she remembered at Woodlands.[30] MacIntosh praises Hannah because “she herself daily took charge of all the lamps in the house”—that is to say, she claimed responsibility for refilling the oil necessary to light the house. MacIntosh’s emphasis on this point suggests that not all housekeepers were as directly involved in domestic labor as Hannah was.[31]

Hannah is described by Charles as possessing an “executive and administrative ability rarely met with in man or woman.”[32] She likely managed the household staff at Woodlands, which in many ways mirrored the running of a business. Furthermore, Charles recounts that Joseph described Hannah and his brother Abraham (the head of the family business) as the most alike.[33] Hannah was, however, only indirectly involved in the family enterprise, such as when Charles wrote to her and Joseph, “I will include thee Dear Aunt H[annah], for my letters to Woodlands seem so lately of a business character that the Uncle [Joseph] must have the bulk of them unless I make thee too the recipient of such.”[34] Although Hannah did not play an active role in the family’s tanning industry, she ran the household with business acumen comparable to Abraham’s.

MacIntosh describes Woodlands as always filled with children, especially Joseph’s and Hannah’s nieces and nephews. MacIntosh attributes this to Joseph’s love of children, but Hannah appears in many of these stories. In one such account, a neighbor’s young daughter is invited to supper, and “perched on the arm of Hannah’s chair she eagerly watched the supper being brought,” before crying at the sight of “steamed crackers.”[35] Though Hannah’s role in this account is all but lost, one can imagine her comforting the crying child in her chair. In 1855, Abraham’s and James’ wives both died. Charles comments that though Hannah was deprived of the “crown of womanhood,” she “possessed those jewels of the crown—service and kindness in the home” and “her devotion to her brothers’ children” after their mothers’ deaths, “that in a large measure made us look up to her as a foster mother,” thus “endowing her with motherhood as possible to one who could not wear the crown.”[36] Significantly, Charles references an ideal womanhood in which the home and childcare are inseparable. Prescriptive books such as Home Influence: A Tale for Mothers and Daughters (1850) by Grace Aguilar spoke to the reliance on women for the “well-doing and happiness, or the error and grief, not of childhood alone, but of the far more dangerous period of youth.”[37] As the emphasis on sentimentality in home life grew, so too did “intensive mothering,” in which the mother or mother figure assumed full responsibility of childcare.[38]

One striking example of Hannah’s voluntary assumption of the maternal role, even beyond her immediate family, is evident in her relationship with the widow Anna Wistar (who in her younger years almost became matron of Radnor Hall at Bryn Mawr) and her daughter Emma. Hannah often visited Emma at school and wrote to Anna of her progress in swimming lessons.[39] After the family moved to England, Emma wrote to Hannah from Kendal Ladies’ College (a Quaker boarding school) with thanks for sending money, with which she intended to buy books.[40] Letters from Hannah to Charles during his school days at Westtown, and later at Haverford College, reflect a deep emotional attachment: “My dear Charlie, I have felt really lonely in the absence of you dear ones.”[41] As an unmarried sister, Hannah assumed the role of a second mother, fulfilling the nineteenth-century ideal of a self-sacrificing, emotionally invested maternal figure.

Hannah expanded this role to her brothers, acting as a networker and “peace-keeper” of the family, thus maintaining social cohesion.[42] In the early modern era, family roles such as “mother,” “sister,” and “wife” could overlap, and “the analogy between a household led by a brother and a sister and one led by a marital couple” was widely recognized.[43] In the nineteenth century, these roles became more discrete as “nuclear” family units increasingly became the norm. Anne D. Wallace introduces two terms to represent these different family structures: (1) “corporate domesticity,” which is “sibling-anchored” and fluid, versus (2) “industrial domesticity” or, as its commonly known, a nuclear family.[44] Her use of the word “corporate” reflects the common occurrence of the “family enterprise” in which business and domestic labor were intertwined.[45] Unmarried siblings were often beneficial, if not crucial, to “corporate domesticity,” assisting in both work and home life and helping to maintain partnerships and cohesion. Discussing business tensions between Abraham (his father) and Joseph and James (his uncles), Charles writes that Hannah’s “sweet gentle appeals… prevented any serious rupture.”[46] He compares the effects of her influence to a “wave…set in motion” that “will continue to expand to an unlimited diameter,” perhaps making her “the prime factor in their greatest achievements.”[47] Hannah appears to have used her unique position as sister, surrogate wife, and foster mother, as well as the sentimentality ascribed to her role in the private sphere, to buttress the family network and business.

Waves of Influence

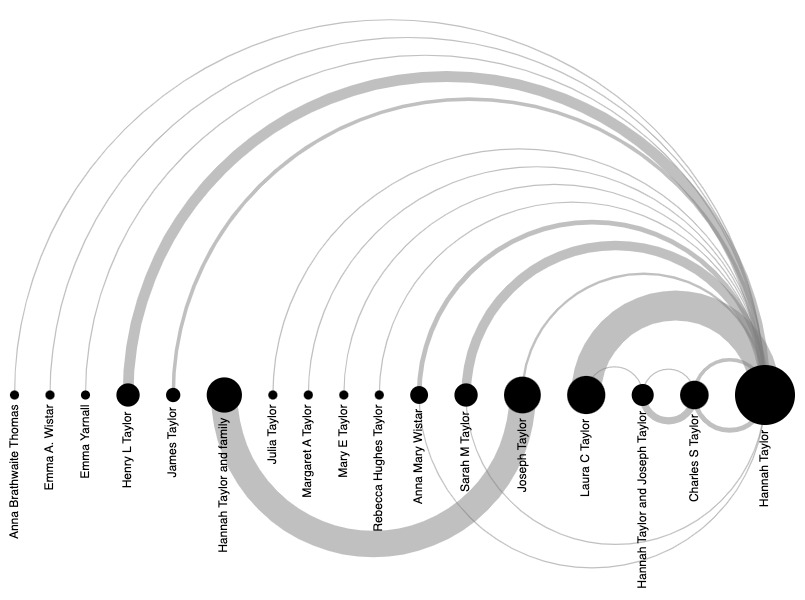

Work within the private sphere was typically not recorded with as much detail as work in the public sphere, leaving large and often invisible gaps in the historical records and archives. Even if all correspondence from Hannah’s lifetime was available, the archive and the medium of letters would still not account for the daily labor she contributed to the family network and enterprise. In Data Feminism (2020) Lauren F. Klein describes a method for visualizing this kind of gap in the archive. She used machine learning to record names mentioned in Thomas Jefferson’s correspondence, mapping them in a network diagram, “Image of Absence”, that visualizes his relationships, and therefore the unacknowledged labor of the enslaved staff working in his kitchens. [48]

Following this model, I collected available data on Hannah’s correspondence between the years 1870 and 1889, including the names of the sender or recipient, to diagram the relationships as well as the silences within these relationships (Table 2). The visualization takes the form of a network graph that displays the degree of correspondence (to, from, and overall) and the relative network connections (Figure 4). Although there are few recorded letters from Hannah during this period, the larger number of letters she received documents the relationships she created and maintained. Furthermore, the significant number of letters addressed by Joseph to Hannah at Woodlands, but with an opening to her and other family members (denoted, for instance, as “Hannah Taylor and family,” “Hannah and nieces, nephews, and brothers,” or “Hannah and Sarah”) suggests not only that she had direct access to her family, but also that she functioned as Joseph’s mediator within the family network when he was absent. Family members, such as their nieces and nephews, would therefore need to communicate with Hannah, whether in person or via correspondence, to receive news of their uncle. However, this graph should be read not only as a reflection of what we know, but also of what we do not know, including the nuances in these relationships, missing interlocutors, and unrecorded communications that helped sustain family ties. The graph shows only the first ripples of Hannah’s eventual waves in the lives of the Taylor family.

In a personal note, Hannah meditates on the importance of her family, and its “great consequence and worth” for “we are bound together by such a tie, that it continues in all its force even in separation.”[49] This statement represents the “corporate domestic” dynamic of the large, dispersed Taylor family, and the strong ties that Hannah established, nurturing familial cohesion despite strain and distance. Although much of her life’s work is lost, or was never recorded, the ripples of her influence can still be visualised through the network she maintained and the accounts of her family members. By working within the domestic sphere, appealing to the sentiments of her family, she helped to maintain the Taylor family’s relationships, and by extension, their business. She also balanced progressively modern and traditional ideals of femininity at a time when women were increasingly excluded from the “public sphere” and work outside of the home.

Domestic Staff

It must be noted, however, that Hannah did not maintain her family’s households alone. She had servants who supported her in caretaking. Domestic staff in nineteenth-century America were often comprised of Irish immigrants, African Americans, and Native Americans (who were forced to attend boarding schools that trained them for domestic service). Their labor is usually rendered invisible, and they themselves are further obscured by the archival exclusion of individuals from non-hegemonic racial and economic groups. Just as the Taylor brothers’ achievements should be assessed with consideration of Hannah’s contributions, recognition of Hannah’s accomplishments must also acknowledge the domestic staff who assisted her. In the 1870 census, Hannah and Joseph are recorded as employing four “domestic servants”: Matilda McGonigal, Bridget Lanahan, Mary Mitchell, and Mary Ford. McGonigal, Lanahan, and Ford had immigrated to the United States from Ireland, while Mitchell was born in Pennsylvania.[50] Lanahan and McGonigal appear again in the 1880 census as the Taylors’ “chambermaid” and “cook,” respectively, and presumably remained with Hannah until her death in 1889.[51]

McGonigal is named in two letters Hannah wrote to Charles in 1865, while he attended Westtown. In the first letter, Hannah light-heartedly writes, “Matilda [McGonigal] says she should love to send thee some ice cream, don’t believe there would not be much ice about it when it reaches thee.”[52] A month later she again mentions McGonigal’s desire to send Charles ice-cream: “Matilda made some cakes for thee when I was from home, wishes she could send thee some ice cream.”[53] These letters not only reveal the nurturing and playful relationship between Charles and McGonigal, but also the support Hannah received in caring for Charles and sustaining their relationship.

It is impossible to argue that Hannah directly influenced the founding of Bryn Mawr College. None of her extant letters name the College, either before or after its opening. Yet, following Lepore’s encouragement to “err on the side of inclusion,” we might still consider whether the College would have been possible without Hannah’s positive influence on the Taylor family and their business ventures.[54] Moreover, Hannah reflects the “high moral and religious attainments and good examples and influence” that Joseph stipulated should be “preferred” in the admission of students to Bryn Mawr.[55] A “beautiful example of self-control,”[56] Hannah would never have fallen prey to the “foolish fashions” and “foolish follies or haunts” that Joseph repeatedly cautions against in his vision for the College.[57] The deep respect that her family felt for Hannah and their admiration of her conduct and character suggest that she exemplified the Quaker lady that Joseph imagined as a Bryn Mawr student. Above all, Joseph believed that the “advanced Christian education” provided by Bryn Mawr would prepare students “for usefulness and influence, should they become mothers, to train infant minds and give directions to character.”[58] The tragic deaths of Hannah’s sisters-in-law that instigated her role as a foster mother likely solidified Joseph’s belief that all Quaker women should be educated in anticipation that they might one day be entrusted with the upbringing of children. It is therefore hard to believe that such a “saintly character” as Hannah could not have influenced Joseph’s vision of ideal Quaker womanhood.[59] In this way, we can appreciate that Hannah also contributed in a fundamental way to the building of Bryn Mawr.

| Word | Count |

|---|---|

| abilities | 1 |

| accuracy | 1 |

| administrative | 1 |

| admirable | 1 |

| advisor | 1 |

| beauty | 2 |

| beloved | 1 |

| capable | 1 |

| careful | 2 |

| charity | 1 |

| common-sense | 2 |

| composed | 1 |

| confidante | 1 |

| devoted | 2 |

| devotion | 1 |

| dignified | 1 |

| discretion | 1 |

| domestic | 1 |

| efficiency | 1 |

| encouragement | 1 |

| exact | 1 |

| example | 1 |

| executive | 1 |

| forceful | 1 |

| foster-mother | 1 |

| gentle | 1 |

| grace | 1 |

| helpful | 1 |

| housekeeper | 1 |

| ideal | 1 |

| judgement | 1 |

| kind | 2 |

| lonely | 1 |

| long-suffering | 1 |

| lovable | 1 |

| love | 1 |

| loveliness | 1 |

| method | 1 |

| methodical | 1 |

| mother | 1 |

| neat | 2 |

| noble | 1 |

| observant | 1 |

| paragon | 1 |

| peace-maker | 1 |

| perfect | 1 |

| practical | 1 |

| pure | 1 |

| quiet | 1 |

| retiring | 1 |

| saintly | 1 |

| self-control | 1 |

| self-sacrifice | 1 |

| service | 1 |

| stimulating | 1 |

| sweet | 3 |

| sympathetic | 2 |

| tactfulness | 2 |

| virtue | 1 |

| wisdom | 1 |

| womanly | 1 |

| From | To | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Anna Brathwaite Thomas | Hannah Taylor | 1 |

| Anna Mary Wistar | Hannah Taylor | 4 |

| Charles S Taylor | Hannah Taylor and Joseph Taylor | 6 |

| Charles S Taylor | Hannah Taylor | 3 |

| Emma A Wistar | Hannah Taylor | 1 |

| Emma Yarnall | Hannah Taylor | 1 |

| Hannah Taylor | Charles S Taylor | 4 |

| Hannah Taylor | Sarah M Taylor | 1 |

| Hannah Taylor | Anna Mary Wistar | 1 |

| Hannah Taylor and Joseph Taylor | Charles S Taylor | 1 |

| Henry L Taylor | Hannah Taylor | 9 |

| James Taylor | Hannah Taylor | 3 |

| Joseph Taylor | Hannah Taylor and family | 22 |

| Joseph Taylor | Hannah Taylor | 2 |

| Julia Taylor | Hannah Taylor | 1 |

| Laura C Taylor | Hannah Taylor | 25 |

| Laura C Taylor | Hannah Taylor and Joseph Taylor | 1 |

| Margaret A Taylor | Hannah Taylor | 1 |

| Mary E Taylor | Hannah Taylor | 1 |

| Rebecca Hughes Taylor | Hannah Taylor | 1 |

| Sarah M Taylor | Hannah Taylor | 8 |

Suggested Reading

Primary Sources

1870 United States Federal Census – AncestryLibrary.Com. Accessed 9 April 2022. https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/discoveryui-content/view/25676602:7163?tid=&pid=&queryId=794a7e98676ecefb2c7e4234b7453136&_phsrc=gqF7&_phstart=successSource.

1880 United States Federal Census – AncestryLibrary.Com. Accessed 9 April 2022. https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/discoveryui-content/view/27733558:6742?tid=&pid=&queryId=076570349730e1f5dfbe2a3e2f0cf920&_phsrc=gqF9&_phstart=successSource

Allinson and Taylor family papers (HC.MC.950.001), Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, PA.

Taylor Family papers, 1755-1930 (HC.MC.962) Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, PA.

Secondary Sources

Aguilar, Grace. Home Influence: A Tale for Mothers and Daughters. New York: Harper and Brothers, Publishers, 1850.

Coleman, Marilyn and Lawrence H. Ganong. The Social History of the American Family: An Encyclopedia. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: SAGE Publications, 2014.

‘Conventions’, Colored Conventions Project (blog), accessed 12 October 2022, https://coloredconventions.org/about-conventions/.

D’Ignazio, Catherine and Lauren F. Klein. Data Feminism. Strong Ideas. Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 2020.

Froide, Amy M. Never Married: Singlewomen in Early Modern England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Lepore, Jill. Book of Ages: The Life and Opinions of Jane Franklin. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2013.

Lerner, Gerda. “The Lady and the Mill Girl: Changes in the Status of Women in the Age of Jackson.” Midcontinent American Studies Journal 10, no. 1 (1969): 5–15.

MacIntosh, Margaret Taylor. Joseph Wright Taylor: Founder of Bryn Mawr College. Haverford, PA: C.S. Taylor, 1936.

Manoff, Marlene. “Mapping Archival Silence: Technology and the Historical Record.” In Engaging with Records and Archives: Histories and Theories, edited by Fiorella Foscarini, Heather MacNeil, Bonnie Mak, and Gillian Oliver, 63–81. London: Facet Publishing, 2016.

McHugh, Kathleen Anne. American Domesticity: From How-to Manual to Hollywood Melodrama. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Richter, Amy G. At Home in Nineteenth-Century America: A Documentary History. New York: New York University Press, 2015.

Sedgwick, Catharine Maria. Married or Single? New York: Harper & Brothers, 1857.

Sedgwick, Catharine Maria. Married or Single? Edited by Deborah Gussman. Legacies of Nineteenth-Century American Women Writers. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2015.

Wallace, Anne D. Sisters and the English Household: Domesticity and Women’s Autonomy in Nineteenth-Century English Literature. Anthem Nineteenth-Century Series. London: Anthem Press, 2018.

Wulf, Karin A. Not All Wives: Women of Colonial Philadelphia. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2019.

Notes

[1] Margaret Taylor MacIntosh, Joseph Wright Taylor: Founder of Bryn Mawr College (Haverford, PA: C. S. Taylor, 1936), 26-31.

[2] Charles S. Taylor, The Taylor and Shoemaker Families, Taylor Family Genealogies, Box 8, Taylor Family papers, 1755-1930 (HC.MC.962), Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, PA.

[3] ‘Conventions’, Colored Conventions Project (blog), accessed 12 October 2022, https://coloredconventions.org/about-conventions/.

[4] Catherine D’Ignazio and Lauren F. Klein, Data Feminism, Strong Ideas (Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 2020), 119.

[5] Jill Lepore, Book of Ages: The Life and Opinions of Jane Franklin (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2013), xii.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Letter from Hannah Taylor to Charles S. Taylor, 9 September 1865, Box 5, Taylor Family papers, 1755-1930 (HC.MC.962), Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, PA.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Charles S. Taylor, Hannah Taylor, 1808-1889, Allinson and Taylor family papers (HC.MC.950.001), Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, PA.

[10] Ibid.

[11] MacIntosh, Joseph Wright Taylor, 20

[12] Taylor, Hannah Taylor, 4-5.

[13] Ibid., 26.

[14] Ibid., 27.

[15] Ibid., 98.

[16] Taylor, Hannah Taylor, 6.

[17] Catharine Maria Sedgwick, Married or Single? (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1857).

[18] These literary works included popular books such as Nathaniel Hawthorne’s House of the Seven Gables (1851) and Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852). Catharine Maria Sedgwick, Married or Single? edited by Deborah Gussman, Legacies of Nineteenth-Century American Women Writers (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2015), xiv.

[19] Karin A Wulf, Not All Wives: Women of Colonial Philadelphia (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2019), 106.

[20] Ibid., 117.

[21] Ibid., 57-58.

[22] Gerda Lerner, “The Lady and the Mill Girl: Changes in the Status of Women in the Age of Jackson,” Midcontinent American Studies Journal 10, no. 1 (1969), 190.

[23] Marilyn Coleman and Lawrence H. Ganong, The Social History of the American Family: An Encyclopedia (Thousand Oaks, Calif.: SAGE Publications, 2014).

[24] Amy G. Richter, At Home in Nineteenth-Century America: A Documentary History (New York: New York University Press, 2015), 11.

[25] Taylor, Hannah Taylor, 1.

[26] “Humility,” copied by Mary Allinson for Hannah Taylor, 27 March 1852, Box 5, Taylor Family papers, 1755-1930 (HC.MC.962), Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, PA.

[27] Lerner, “The Lady and the Mill Girl,” 191.

[28] Kathleen Anne McHugh, American Domesticity: From How-to Manual to Hollywood Melodrama (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 15-59.

[29] Ibid., 23.

[30] MacIntosh, Joseph Wright Taylor, 31.

[31] Ibid. I thank Alexis White for pointing out to me the specific phrasing of this sentence.

[32] Taylor, Hannah Taylor, 3.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Letter from Charles S. Taylor to Hannah and Joseph Taylor, 3 December 1879, Box 4, Taylor Family papers, 1755-1930 (HC.MC.962), Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, PA.

[35] MacIntosh, Joseph Wright Taylor, 170.

[36] Taylor, Hannah Taylor, 2.

[37] Grace Aguilar, Home Influence: A Tale for Mothers and Daughters (New York: Harper and Brothers, Publishers, 1850), vii.

[38] Marilyn Coleman and Lawrence H. Ganong, The Social History of the American Family: An Encyclopedia (Thousand Oaks, Calif.: SAGE Publications, 2014).

[39] Letter from Hannah Taylor to Anna M. Wistar, 1 September 1877, Box 8, Taylor Family papers, 1755-1930 (HC.MC.962), Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, PA.

[40] Letter from Emma Wistar to Hannah Taylor, 10 June, from Ladies’ College Kendal, Box 8, Taylor Family papers, 1755-1930 (HC.MC.962), Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, PA.

[41] Letter from Hannah Taylor to Charles Taylor, 9 May 1865, Box 5, Taylor Family papers, 1755-1930 (HC.MC.962), Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, PA.

[42] Taylor, Hannah Taylor, 15.

[43] Amy M. Froide, Never Married: Singlewomen in Early Modern England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 74.

[44] Anne D. Wallace, Sisters and the English Household: Domesticity and Women’s Autonomy in Nineteenth-Century English Literature, Anthem Nineteenth-Century Series (London: Anthem Press, 2018), 27.

[45] Ibid., 28.

[46] Taylor, The Taylor and Shoemaker Families, unpaginated.

[47] Ibid.

[48] D’Ignazio and Klein, Data Feminism, 160-61.

[49] Personal note by Hannah Taylor, 1857, Box 5, Taylor Family papers, 1755-1930 (HC.MC.962), Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, PA.

[50] 1870 United States Federal Census – AncestryLibrary.Com, accessed 9 April 2022, https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/discoveryui-content/view/25676602:7163?tid=&pid=&queryId=794a7e98676ecefb2c7e4234b7453136&_phsrc=gqF7&_phstart=successSource.

[51] 1880 United States Federal Census – AncestryLibrary.Com, accessed 9 April 2022, https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/discoveryui-content/view/27733558:6742?tid=&pid=&queryId=076570349730e1f5dfbe2a3e2f0cf920&_phsrc=gqF9&_phstart=successSource.

[52] Letter from Hannah Taylor to Charles S. Taylor, 9 May 1865. Box 5, Taylor Family papers, 1755-1930 (HC.MC.962), Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, PA.

[53] Letter from Hannah Taylor to Charles S. Taylor, 2 June 1865, Box 5, Taylor Family papers, 1755-1930 (HC.MC.962), Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, PA.

[54] Lepore, Book of Ages, 270.

[55] Joseph W. Taylor, “Will of Joseph Wright Taylor,” Box 7, Taylor Family papers, 1755-1930 (HC.MC.962), Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, PA.

[56] Taylor, Hannah Taylor, 11.

[57] Joseph W. Taylor, “Will of Joseph Wright Taylor” Box 7, Taylor Family papers, 1755-1930 (HC.MC.962), Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, PA.

[58] Joseph W. Taylor, “Will of Joseph Wright Taylor” Box 7, Taylor Family papers, 1755-1930 (HC.MC.962), Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, PA.

[59] Taylor, The Taylor and Shoemaker Families, unpaginated.