Orientalism at the Deanery

Although it began as a five-room cottage, by the time of her death in 1935, M. Carey Thomas had transformed her home, The Deanery, into an opulently appointed mansion. Thomas collected furniture and art from China, Japan, Egypt, India, and Syria for her home and garden, despite regularly expressing her hatred for non-white people and her support for eugenics in her journals, letters, and even public speeches.

Thomas’ collection of Asian art revealed a larger system of Orientalism. White Europeans and Americans often collected art, especially Asian art, while supporting policies that excluded the very people who made it. Imitations of Asian antiquities were mass produced for department stores and sold as authentic to fashionable white households. Rather than appreciation, its display reinforced imperialism and Western dominance over an imagined primitive and unchanging Asia. This art, everywhere in the Deanery, surrounded everyone who entered – including students, staff, and faculty of the college.

Deanery Decor

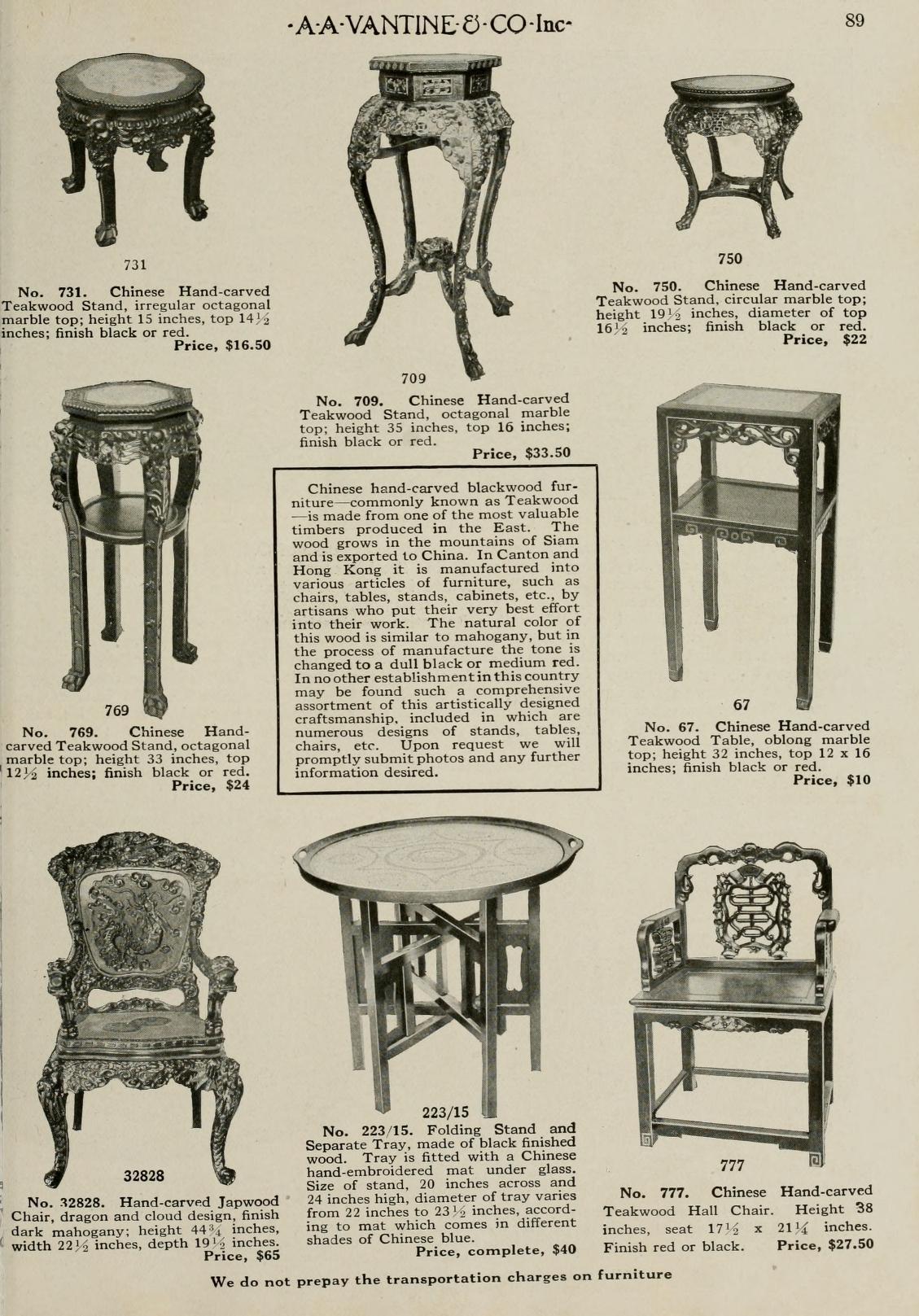

A. A. Vantine Plant Stand

This plant stand for the Deanery, likely purchased by M. Carey Thomas, came from A. A. Vantine’s, a New York City department store that sold Asian-inspired furniture to a middle or upper class American clientele. The text and images used in Vantine’s ads marketed Asia as unthreatening and ripe for Western consumption.

The stand’s carved teakwood base features bat (蝙蝠 biān fú) motifs, which in Chinese sounds similar to the word for happiness (幸福 xìng fú). Such details, however, were ignored by Western consumers. A. A. Vantine’s made their fortune by selling objects like this plant stand as exotic and luxurious – while disdaining the actual people and cultures who created these pieces.

Buddha Statue

This Buddha statue was one of many that decorated the Deanery. It shows a variation of the dhyana mudra, where the thumb and pointer fingers curl in towards each other to make two circles. This variation of the gesture distinguishes the Buddha statue as an Amitabha Buddha also known as the Buddha of Eternal Life. Though Thomas had several Buddha statues in her home, her letters and speeches indicated that she did not respect Buddhism as a religious practice. Attitudes like Thomas’s prevailed across the US, with wealthy, white Americans often seeking to purchase mystic, exotic objects without further education – reducing non-Christian religions into a commodity to satiate American consumerism.

The Deanery Garden (Taft Garden)

Thomas went to great lengths to fill her personal garden (now Taft garden) with an eclectic collection of Asian and Middle Eastern objects. On a 1915 trip to Beijing, Thomas brought back a pair of two stone lions that were claimed to be over 1000 years old. The stone statues were placed facing inward, instead of the conventional outward direction. Around the garden, there were also several Japanese stools, like the one seen here, which were common in American homes attempting to recreate an Asian aesthetic.

Chinese Porcelain in the West

By the 16th century, Chinese merchants were exporting porcelain to Europe. Shipped from Canton (now Guangzhou), the ceramics became known in English as “Canton Ware.” The porcelain was highly praised for its translucence and unique blue glaze designs. In Western countries, owning Chinese porcelain was a sign of wealth and prestige, which likely motivated Thomas’ collecting of it. As Chinese porcelain became popular, Chinese artists catered their designs toward European audiences by incorporating Western motifs. In the present day, Canton ware is more likely to be found in a white American household than a Chinese one.

M. Carey Thomas Abroad

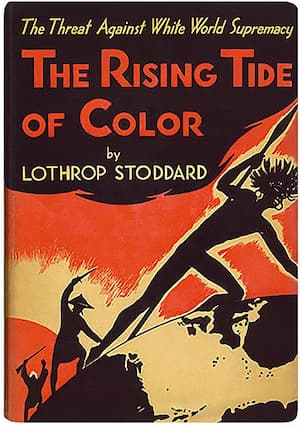

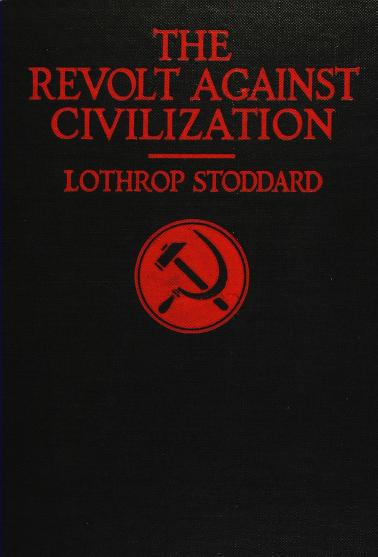

Although Thomas decorated the Deanery with art from around the world, she remained intensely hateful towards non-Western cultures. In a 1922 letter to family from Bombay, Thomas discussed her avid support of Lothrop Stoddard, prominent American eugenicist, KKK member, and, later, Nazi. She recommended her family read The Rising Tide of Color (1920) and Revolt Against Civilization (1922). The books advocated for strict, selective immigration and eugenics practices to preserve white racial purity.

“It is not only our duty to try to give a good heredity to our children but also to try to control the heredity of our nation and of our race. Nothing else in the world seems to me quite so important as this.” — M. Carey Thomas