Japanese and Chinese Scholarships

The Beginning of the Japanese and Chinese Scholarship Program (1893-1985)

Bryn Mawr’s first Japanese student, Tsuda Umeko, came to the College in 1889 as a special student. Her speeches to the Quaker Women’s Foreign Missionary Association of Friends of Philadelphia (WFMA) convinced funders, such as Mary Morris, to establish an “American Scholarship for Japanese Women.” Tsuda hoped scholarship recipients would return to Japan from the U.S. to become teachers, just as she had done, helping to elevate the status of Japanese women. Although the WFMA insisted the scholarship be open to all Japanese women, they set the admission test in English, limiting candidates to those with a language proficiency only available to students at Christian missionary schools. Matsuda Michi became the first recipient of the Japanese scholarship in 1893.

By 1916, other colleges had begun admitting Chinese students, spurring Bryn Mawr to establish The Chinese Scholarship. Having recently taken a sabbatical trip to China, English professor Lucy Martin Donnelly (Class of 1893), volunteered to lead this endeavor. Her committee recruited applicants from many of the Christian colleges in China where Bryn Mawr alumnae had taught. Liu Fung Kei, a student at Canton Christian College, was the first recipient of the Chinese Scholarship. She arrived at Shipley School in 1917 to prepare to enter Bryn Mawr the following year.

Scholarships for Whom?

“Acquaintance and friendship with modern Chinese girls should give more reality to the study of their ancient arts and should add greatly to the variety and interest of campus life…. It should have something of the color of adventure, of reaching out into new regions of interest.” — Lucy Martin Donnelly

Lucy Martin Donnelly’s characterization of the Chinese Scholarship emphasized its value to white students, rather than to the Chinese students themselves. Although she graduated in the year prior to the scholarship’s formation, Helen Burwell Chapin (Class of 1914, BA 1915) is the type of student the Committee hoped the Chinese scholarship would benefit.

Following graduation, Chapin worked as a stenographer in the Oriental Art department of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, where she developed the enthusiasm for East Asian culture that would become her life-long devotion. She traveled extensively through Asia, studying East Asian languages and culture, and eventually earning a Ph.D. with a thesis on a pair of swords. She became a research analyst in Chinese and Japanese for the U.S. Department of Justice, and later the Arts and Monuments Specialist for the U.S. Army in Korea.

Upon her death, Chapin gave her rich collections of books and art to Bryn Mawr College. These materials reflect her deep knowledge of East Asian cultures, even as they include several items that misrepresent East Asian as antiquated, primitive, and exotic to Western eyes.

Chapin’s Collection

Clerical Script

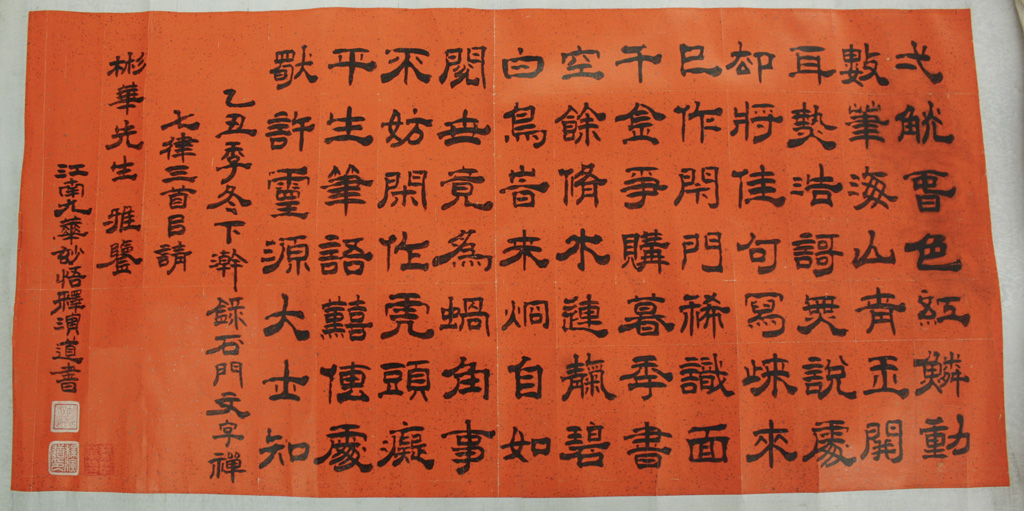

During Chapin’s first visit to China in 1925, a Buddhist monk gave her this transcription of a Buddhist poem from the Song Dynasty. The transcription contains her Chinese first name (彬華) and signals his recognition of her sincere academic interest in Buddhism, poetry, and art. During her second trip to China on a research fellowship through Swarthmore College, Chapin was invited by the Palace Museum in Beijing to help identify several Buddhist statues.

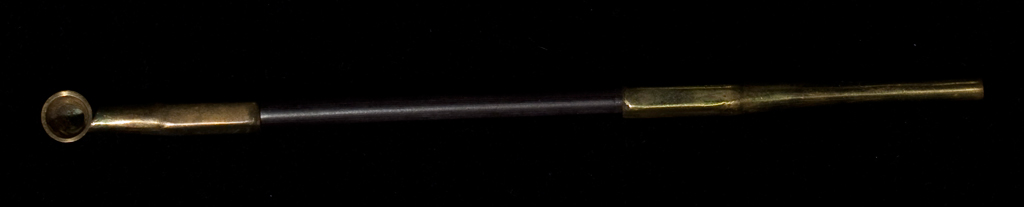

The Opium Pipe

This small pipe is designed for smoking opium. Even though opium pipes are associated with East Asian cultures, opium only entered these countries due to Western influence. Britain attempted to economically colonize China by selling opium and making China dependent on trade. In the US, as anti-Chinese sentiment rose, the stereotype of Chinese workers smoking opium and being lazy spread. Collecting this pipe echoes the Western imperialism in East Asia.

Shoes for bound feet

Although the practice of binding women’s feet ended by the 20th century, Americans continued to be fascinated by the practice, which they deemed exotic and strange. Multiple Chinese women with bound feet were brought to America and put on display in public to be gawked at. Most famously, the first Chinese woman to come to America, Afong Moy, was taken from China in 1834 and exhibited in a fake Chinese salon with posters headlined “The Chinese lady with astonishing little feet.” Chapin’s collection of such objects may have participated in this spectacle.