The earliest record of using screens in China can be dated to the West Zhou period (1046-771 B.C.), “The emperor stands in front of the screen and the vassals pay homage to him.”1 The screens in the earliest time represented the status and power of the owners. The Chinese have been making screens with decorations since the Warring States period (475-221 B.C.) at the latest.2 Although screens could have a didactic function and an honorific function, their primary purpose has always been to protect and conceal. In History of the Former Han, Sima Qian (c. 145-c. 86 B.C.) wrote that when a royal talked with guests, his historian hid behind a screen to write down their conversation.3 Women could not be seen by men other than immediate relatives according to Confucian ethics, so they watched musical and dance performances, listened to the conversation between their husbands and guests, and even joined in discussions behind a screen.4

Chinese Screens were transported to Europe as early as the 17th century. Most of the screens exported to Europe were black with gold-traced paintings. Artisans would smooth and polish the wooden pieces first, then coat the lacquer. After the lacquer dried, pierced paper with the draft of the design on it would be covered on the wooden pieces. A kind of powder would be sprinkled through the holes to transfer the patterns to the wood. Artisans would then use orpiment first to make sketches, followed by outlining with sharp-pointed painting tools, and complete the paintings in red bole. Finally, they would adhere to gold dust before the bole dried completely.5

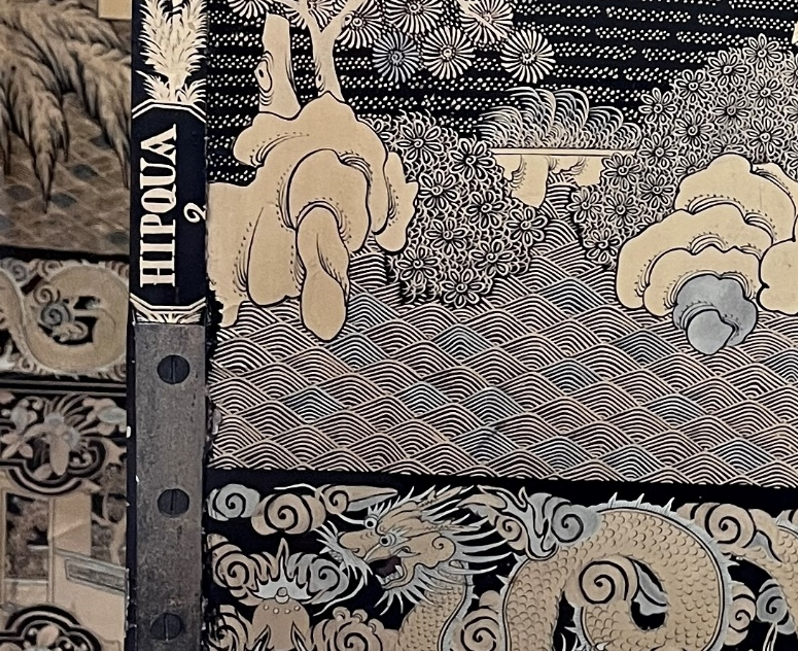

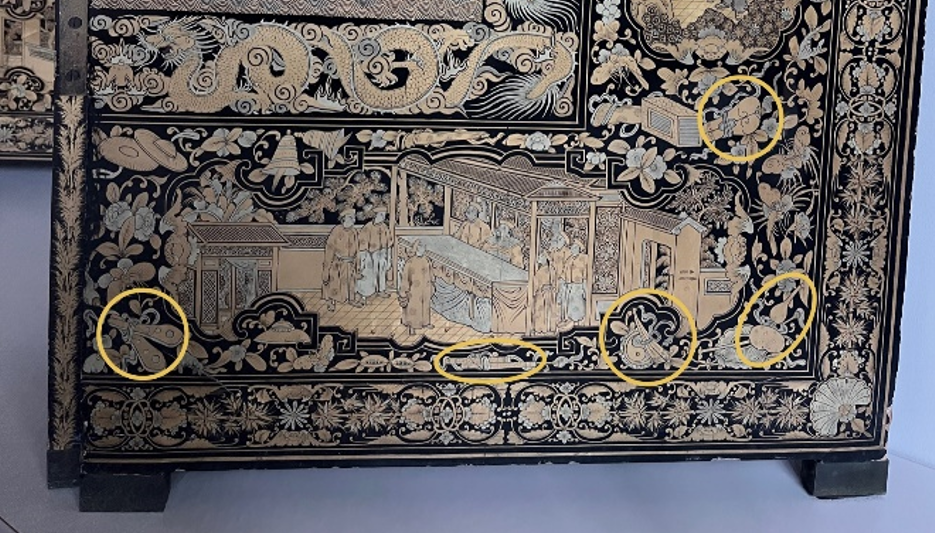

Canton (now Guangzhou) played an important role in the supply chain as it was a place where screens were usually finished and shipped because the thirteen factories area in Canton used to be the only legal place in China for foreign merchants to trade and reside. Therefore, European and American merchants anchored off and ordered products there,6 and it soon became a place for Chinese craftsmen and merchants to do export business. If you check the side of the screen, you can see “HIPQUA” is written on it. This indicates that this screen was made by the Hip Qua workshop. The workshop was located at New China Street, one of the three main shopping streets in thirteen factories area in Canton.7 Hip Qua was not the real name of the workshop. It was the Romanized name of the shop owner given by European merchants, and it was difficult to match the artifacts made by Hip Qua because the name was addressed differently in different languages.8

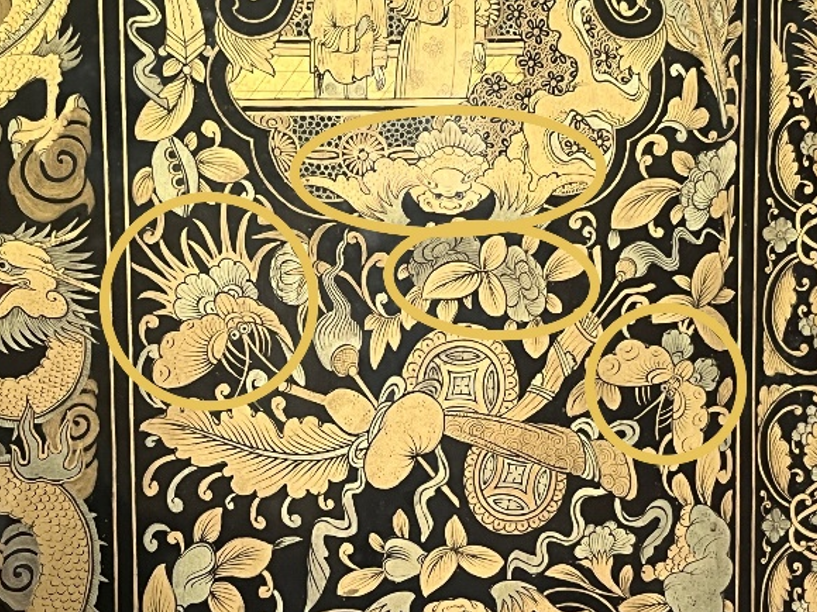

This screen is decorated with the patterns of ritual tools that symbolize eight immortals in Daoism. The figures of eight immortals can be seen frequently in Chinese artifacts. They represent longevity, and carefreeness in the Chinese cultural context. You can also see the patterns of bats and butterflies on the screen. One of the characters of bats in Chinese (蝙蝠,biān fú) has the same pronunciation as one of the characters of happiness in Chinese (幸福, xìng fú), therefore, the motif of bats is often used in traditional Chinese furniture. Motifs of butterflies symbolize prosperity, which often appears together with peonies.9

The meanings of motifs on the screen might have been ignored by the merchants and collectors. Asian goods and people were usually featured as public spectacles for Americans, especially after the mid-nineteenth century.10 The catalogs of department stores and magazines provided detailed models for women to follow to decorate their homes in an Oriental style.11 As the commodification of Asian goods became more prevailing in middle and upper-class women’s homes in the early twentieth century, Asian objects were confined in certain domestic spaces. They were kept as a subordinate element to show the presence of exotic otherness and artistic taste of the hostesses.12 As long as the Asian objects were kept as a seasoning and no more than artistic whimsy, they were still appreciated. Americans subtly and carefully separated Asian arts from their cultural and historical contexts commodified them as objects and restricted them as “slight impressions” at American homes,13 which is also why we can see this screen at Carpenter Library as one of Marion Edwards Park’s collections.

-

《逸周书···卷六···明堂解》 ↩

-

Handler Sarah, Austere luminosity of Chinese classical furniture. ↩

-

《史记···孟尝君列传》 ↩

-

Handler Sarah, Austere luminosity of Chinese classical furniture. ↩

-

Petisca, M. J., J. C. Frade, M. Cavaco, I. Ribeiro, A. Candeias, J. Graça, and J. C. Rodrigues. “Chinese export lacquerware: characterization of a group of Canton lacquer pieces from the 18th and 19th centuries.” 2011, p2. ↩

-

Farris Jonathan, Thirteen Factories of Canton: An Architecture of Sino-Western Collaboration and Confrontation, p66. ↩

-

Hong Kong Museum of Art, to my friends travelling to Canton, 2022. ↩

-

Petisca, Maria João dos Santos Nunes. Investigations into Chinese export lacquerware: black and gold, 1700-1850. University of Delaware, 2019, p58. ↩

-

Chen Xinge, Hou Lingling, Research and Application of Butterfly Pattern in Qing Dynasty, p2. ↩

-

Yoshihara, Mari. Embracing the East: White women and American orientalism. Oxford University Press, 2002, p18. ↩

-

Ibid., p41. ↩

-

Ibid., p42. ↩

-

Ibid., p43. ↩